Louis Armstrong’s 1969-1971 Tapes: Reels 66-70

The last several posts in this series have been filled with dubs of Armstrong’s own recordings (I still might make good on my threat to create a playlist that mirrors these tapes), something that continues in today’s post, but Armstrong also begins to drift a bit here, reaching back to 78s, dubbing Dr. Martin Luther King’s funeral coverage, and recording the audio of his televised comeback appearance. Not to mention the collages in this post are a knockout–let’s dive in!

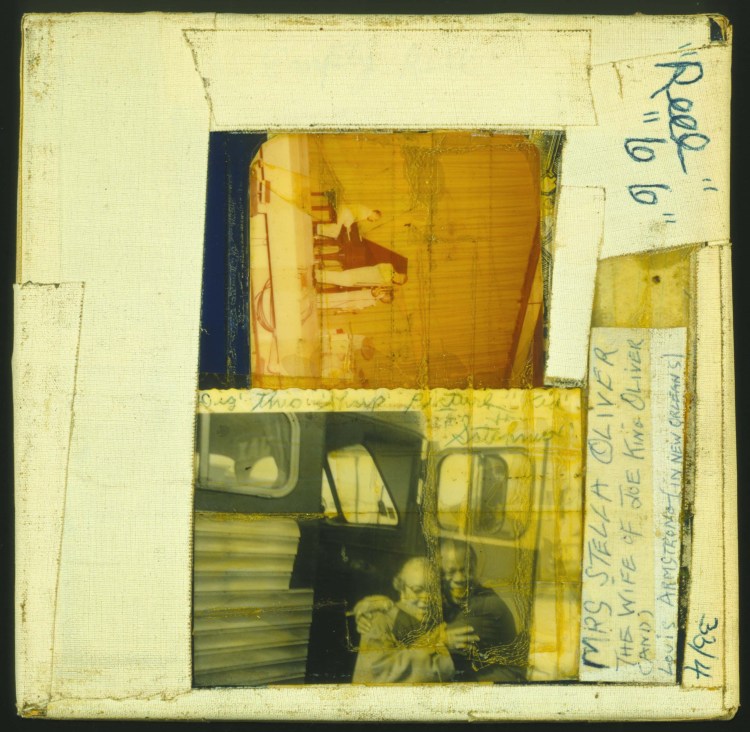

Reel 66

Accession Number: 1987.3.366

When we last left off, Armstrong was dubbing a Parolophone reissue series of his 1925-1928 OKeh recordings titled His Greatest Years. That series concludes at the start of Reel 66 with the remaining 1928 sides made with Earl Hines–before Armstrong starts all over again, this time with the V.S.O.P. (“Very Special Old Phonography”) series on the Odeon label, which begin with the first Hot Five sides from 1925 and continue from there.

The collages on Reel 66 are terrific, though the first one might be difficult to take in at first as there’s stuff taped to it from almost every conceivable angle. We’ve chosen to rotate it because, even though that puts “Reel 66” a bit askew, it focuses the main event, a charming photo of Louis and Stella Oliver, King Oliver’s widow, taken during one of Armstrong’s trips back to New Orleans in the early 1950s. If you flip the box upside down again, you’ll seen Armstrong’s annotation, “MRS. STELLA OLIVER, THE WIFE OF KING OLVER (AND) LOUIS ARMSTRONG–(IN NEW ORLEANS).” Just over the photo is another handwritten caption, “Dig this sharp picture of us, Kid. From Satch.” Clearly it was meant for someone else’s eyes, but we’re glad it ended up here. And if you flip the box one more time, you’ll see a faded color snapshot of the All Stars in action, with Louis and Trummy Young at the microphone and Billy Kyle at the piano:

For the flip side, Armstrong must have had a concert program lying around from the short-lived edition of his band that existed for a few months at the end of 1953 and beginning of 1954. Here they are, individually cut out from left to right: Velma Middleton, Billy Kyle, Barney Bigard, Kenny John, Milt Hinton, and Trummy Young:

Reel 67

Accession Number: 1987.3.367

The music on Reel 67 is pretty straightforward, a continuation of the V.S.O.P. series picking up with the Hot Seven recordings, the final Hot Fives, his recordings backing up vocalist Lillie Delk Christian, and the 1928 Earl Hines sides once again:

The collage on Reel 67 has long been one of our favorites. On the front is a congratulatory telegram Louis received at the Hollywood Bowl from Otis Rene, one of the composers of “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South,” each line clipped out and rearranged in a striking diagonal fashion by Armstrong:

On the back, our first glimpse (I think?) of the famous “Leave It All Behind Ya” Swiss Kriss “keyhole” card paired with a couple of snapshots and another humorous creation of a giant Louis head placed on top of a tiny cartoon body:

Reel 68

Accession Number: 1987.3.368

There’s some interesting things to point out right from the top of the catalog pages for Reel 68. The process of cataloging the content of the tapes and making the collages on the outer boxes was usually separate, but here, Armstrong immediately calls attention to a photo of himself with his mother Mayann and sister Beatrice that is on the front of this particular box. He then continues the V.S.O.P. series with the final 1928 recordings and his earliest big band sides as leader covering the year of 1929. With a little bit of room left of Side 1, Armstrong filled it up with something completely different: the four Italian sides he made in 1968 where, yes, he sang in Italian!

Side 2 also opens with something different, Armstrong’s immortal Decca recordings with the Mills Brothers. Armstrong then reached for Clasicos Del Jazz–which he tells us is “(Spanish)” and was “Issued in Spain”–a compilation of his 1920s sideman work with Erskine Tate, Johnny Dodds, Lil’s Hot Shots, and the Red Onion Jazz Babies. (I always like when a musician catches Armstrong’s ear and he decides to list that person’s name; in the case of the Erskine Tate recordings, Armstrong highlights “Teddy Weatherford, piano, Jimmie Bertrand, washboard.”) The reel concludes with Armstrong’s earliest 1923 recordings with King Oliver, reissued on something he describes as “London Original Del Jazz”:

Another dazzling collage adorns Reel 68 with more paraphernalia from Louis’s “Dixieland Jubilee” concert that took place at the Hollywood Bowl on September 12, 1959. Once again Louis is in a diagonal mood, clipping his name, the names of the producers, a description of the concert, and the words “Dixieland Jubilee” and taping them at angle (while the photo of him playing at the top of the collage is facing the opposite direction).

And finally, the photo of Louis with his mother and sister that he called out in his catalog pages. The text, a dramatic, three paragraph description of his later playing, was originally published in the Sunday Observer on May 13, 1956 and used in his British concert programs (even the title, “Profile Louis Armstrong,” makes an appearance on the front of the tape box, separated and affixed to either side of the photo of him playing).

For those who can’t read it, this passage states, “In the 1940s – and particularly after the last war – there was a rather self-conscious movement to return to the roots of jazz and to smaller, more intimate bands. But for Armstrong there was no need to seek the origins, for he was, virtually, jazz. The only change was that his playing became purer, stripped of frills. With his All-Stars to-day he is more relaxed and smoother than in the past, but as technically brilliant as ever, with that superb tonal sense. He can always keep the tempo alive in the slowest number; any tempo other than his seems wrong. He is probably the only trumpeter of his age who has kept his technique and his strength. He will almost certainly keep on playing until his great teeth go; and they look good for plenty yet. He conserves his energy to-day like an ageing but still great boxer. When you hear him, that fine, hopeful tone could be no one else’s.”

Reel 69

Accession Number: 1987.3.369

Armstrong must have had a pile of Spanish reissues of his music as Reel 69 opens with Louis Armstrong da Nueva Orleans a Nueva York, a compilation of his late 30s and 40s (originally issued in the 78 era as Louis Armstrong Classics: New Orleans to New York).

Then, after all these sleek LPs, Armstrong reaches for something different: his 78-rpm recordings! I won’t list them all–he did that work for me–but it’s interesting to see “Black and Blue,” “When You’re Smiling,” and “All of Me” from that glorious 1929-1931 period before Armstrong dubs a slew of V-Disc, including his own sides, naturally (nice to see the discographical personnel listed in his handwriting) but also sides by Charlie Shavers, the Benny Goodman Quintet, Art Tatum, Fats Waller, Muggsy Spanier, Pee Wee Russell, and more.

(If you’re curious, “A Fast Number – Sounds Like Roy Eldridge,” is “Bugle Call Rag” featuring Charlie Shavers!)

Lucille is the subject of the front of collage Reel 69, with Louis reaching way back for a clipping from her days as a “Dark Dancer” with “Blackbirds of 1936” in London, three full years before she met Louis.

For the rear of Reel 69, Armstrong chose an autographed photo of Lara Saint Paul, the Italian singer he had befriended during a trip to San Remo in 1968, trading correspondence with her and her husband, Pier Quinto Cariaggi, until his passing. (And in case you’re wondering, there’s no doubt in my mind, knowing Armstrong’s sense of humor the way I do, that it was no accident that he chose photos of beautiful women to adorn Reel 69!)

Reel 70

Accession Number: 1987.3.370

With Reel 70, we enter sacred territory. Armstrong was devastated by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 to the point of threatening to boycott the Academy Awards if they didn’t postpone in the wake of King’s murder (the ceremony was postponed in the end). Reel 70 features a recording of King’s funeral service, which had a deep impact on Armstrong, inspiring him to record “We Shall Overcome” later in 1970. It has been assumed, including by staff at the Louis Armstrong House Museum, that Armstrong himself recorded the funeral in 1968 and didn’t get around to cataloging it until 1970, but a closer listen to the tape shows that it also features seamless editing of all the news coverage of King’s murder, too. This is because this tape was actually sent to Louis by his friend Tony Janak, a CBS engineer who made a living out of professionally recording audio of television broadcasts (a quick Google search shows Janak recordings of Harry Truman, Spiro Agnew, Neil Armstrong, and many other historic figures located in major libraries and special collections across the country; Janak donated 5,000 tapes to the Voice Library at MSU in 1981). The original reel was separated from the original box and turned into something new, but in our next post, you’ll see Janak’s original case.

Over the next two years, Janak would regularly send Armstrong tapes with recordings of his TV appearances, but also other things he thought the trumpeter would like, such as coverage of the 1969 moon landing and a recording of radio bloopers, which we’ll come to in due time. For now, though, here’s Armstrong’s page on the coverage of Dr. King’s funeral (a page reproduced and placed on his desk at the Louis Armstrong House Museum):

And now a special treat–the full audio of this portion of the tape (as always, watermarked with subtle beeps to prevent any commercial uses but for historic and research purposes, we think it’s definitely worth sharing). Here is part one:

And part two:

On the flip side, another clue that we’re in early 1970: a dub of Armstrong’s appearance on The Dick Cavett Show on January 13 of that year. Video no longer survives of that appearance, which is probably a good thing. Armstrong hadn’t performed in public since September 1968 and was determined to show he was back, so he brought along his trumpet and soloed on an extended version of “Someday You’ll Be Sorry,” as well as “Pretty Little Missy,” both his own compositions (Joe Glaser left Armstrong all of his shares of his publishing company, International Music, upon his passing in June 1969, so Armstrong was now getting an extra taste every time he performed or recorded his own songs). Unfortunately, it proved to be too much, too soon and Armstrong ran out of gas on live TV, leading to some devastating reviews in the press (“Someone should pass a TV rule forbidding Louis Armstrong from playing his trumpet on the air,” Bob Talbert wrote. “His singing on the Dick Cavett show was great, but Satchmo’s lip is a mere shadow and his playing was embarrassingly weak.”).

Armstrong didn’t let it get him down, though; instead, he sent copies of the performance to Oscar Cohen, who succeeded Glaser as Armstrong’s new representative at Associated Booking, insisting it was proof that he could go back to performing again, just with his trumpet and book of arrangements, fronting orchestras in all the major cities. It wasn’t to be and though Armstrong returned to television more frequently in the coming months, he left his trumpet at home. But in the meantime, he actually dubbed this appearance to multiple tapes, as will be illustrated in our next post–and for now, we’d like to share the watermarked audio of it, too! It’s particularly appropriate for this series as Louis gives a detailed explanation of how he’s been spending his time at home, making tapes, even describing his den and some of what he had been listening to.

Without further ado, here’s the full 42-minute (!), with Cavett’s intro, “Someday You’ll Be Sorry,” multiple interview segments (one of which includes a clip from the film Hello, Dolly!), and a closing “Pretty Little Missy”:

After the digression through Dr. King’s funeral and his appearance on Cavett, Armstrong returned to the theme of Reel 69, closing out Reel 70 with a selection of 78s, again leaning on V-Discs (Art Tatum, Fats Waller, Hot Lips Page’s “Miss Martingale”), and his own (“Home,” “If I Could Be With You,” an unissued test pressing of a duet with Velma Middleton on “Mack the Knife,” and “Star Dust,” running out of tape on the latter).

Armstrong knew the contents of this tape were special and notated on both sides of the outer box that it contained material related to Dr. King. (At the time he made the collage, Side 2 must have been empty but as described above, he soon filled it up.) He also dug up a newspaper comic from 1939, when Armstrong was doubling in Swingin’ the Dream on Broadway and headlining a revue at the Cotton Club (where he met Lucille):

On the reverse, another shoutout to Dr. King, framing a creatively rearranged review in the December 13, 1969 issue of Record World, giving four stars to his single of “We Have All the Time in the World” and “Pretty Little Missy.”

After spending so much of 1969 convalescing and out of the spotlight, it must have been gratifying to have a well-reviewed single, a major motion picture (Hello, Dolly! also opened in December 1969) and to be back on television with the Cavett appearance, all in the span of a few weeks. Armstrong was not quite ready to go back on the road yet, but he was still warming up on trumpet every day at home and he he still had more than one hundred more reel-to-reel tapes in him–and we’ll continue detailing each and every one right here!