“Someday You’ll Be Sorry”: The End of Louis Armstrong and Alpha Smith’s Marriage

In our previous post, we covered the marriage of Louis Armstrong and Alpha Smith, which occurred in Houston on October 11, 1938. In 1940, Louis and Alpha moved from the Hotel Olga to the Hotel Currie at 145th Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem and things appeared to be happy, at least from the outside. “You must meet my Alpha (my little hatchetmouth wife),” Louis wrote to Elmer Lewis on July 16, 1940, adding, “All the musicians – Actors – Record Fans – and everybody has met the Madam Armstrong…”

But by the time he wrote those words, Louis was finding ways to spend more time with dancer Lucille Wilson, whom he met at the Cotton Club during a run that lasted from September 1939 through May 1940. By the fall of 1940, Louis felt comfortable enough taking Lucille–not Alpha–on a tour of the “Deep South” as noted on the back of this snapshot:

In the fall of 1940, Columbia Records released its first reissue of Armstrong’s Hot Five recordings in album form, produced by Yale student George Avakian. Avakian brought a copy to Louis, who said he wanted to give it to his “sweetheart”–taking him to see Lucille. Both Avakian and Armstrong signed the copy of King Louis–Avakian wrote, “Lucille, I hope you go for this Louis fella and these records for a long time,” and Louis added, “Yes ma’am”–and it remains in our Archives to this day.

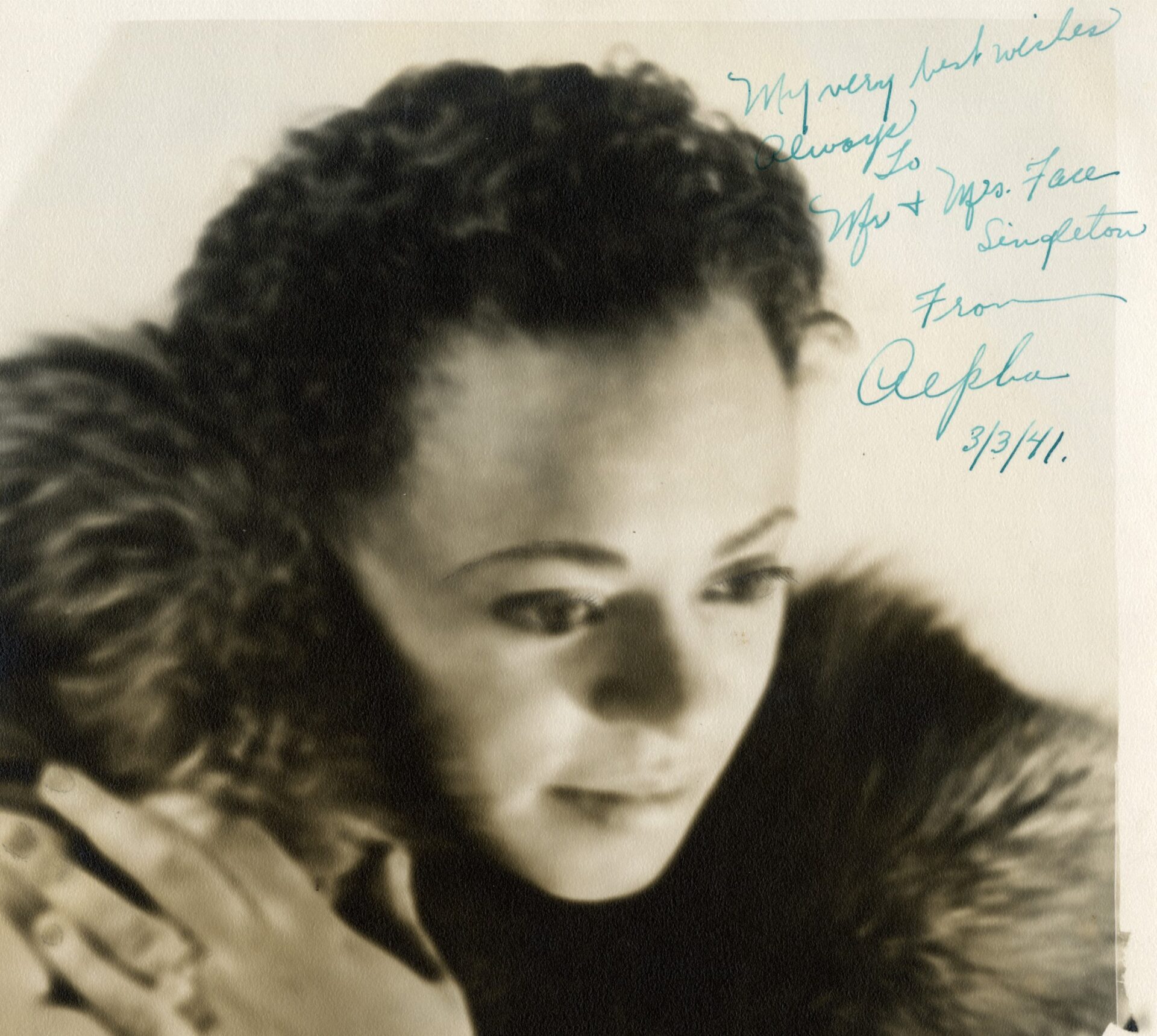

By this time, according to Louis, Alpha was drinking more and more. Alpha took a new publicity photo in October 1940–quite possibly while Louis was on the road with Lucille–posing in her signature fur. She eventually signed a copy of her new photo for drummer Zutty Singleton and his wife Marge on March 3, 1941. Perhaps I’m looking too deeply into it, but the light seems to have gone out of Alpha’s eyes; there’s a somberness here that wasn’t present in those mid-1930s photos:

Alpha was still seemingly on the outs a few months later, Louis’s big band toured Canada in late May and early June 1941. As they crossed the border, a photograph was taken of the entire band–and Lucille Wilson, hoisted in the air on the shoulder of Big Sid Catlett (that’s Louis’s handwriting, identifying all the members):

Thus, Lucille was clearly making herself at home with Louis and the band in the summer of 1941. And sure enough, in the eventual divorce papers of Louis and Alpha, filed by Louis on July 21, 1942, Louis claimed that on “the 28th day of June, 1941, the Defendant [Alpha] willfully deserted and absented herself from the Plaintiff [Louis] without any reasonable cause and without fault on his part, and has persisted in such desertion, and yet continues to absent herself from the Plaintiff for the space of one year immediately prior to the filing of this Complaint.”

However, that seems to be an arbitrarily chosen date to illustrate that they had been separated for a full year; in actuality, Alpha gave it one more go, once again traveling with Louis on the road in September 1941 and making cameos in a few letters Louis wrote to Leonard Feather during this time. On September 18, Louis wrote from Atlanta, marveling at how “the colored folks and the white folks” danced at a recent performance. “Alpha Kills me when she sits on the bandstand some night and watch them,” he wrote. “She said she watches them for so long and concentrating on them too – She said she gets the ‘swimmin in the head..ha..aha..So you can tell by that – that they really Jumps for Joy….No Foolin…”

Two days later, Louis wrote to his manager Joe Glaser to let him know about a “Nine Day Diet” Alpha had put him on:

Armstrong then included the diet chart, credited as being “By Alpha Armstrong For herself and Louis Armstrong”:

On October 1, Louis wrote a long letter to Feather from Panama City, Florida. In it, he referenced Alpha’s diet chart, crediting her as getting it from “Vague” Magazine! He writes:

In that same October 1 letter to Feather, Armstrong shared details of a recent performance for soldiers in Pensacola, where he bonded with Private George Grow. “So George and I went on into the house where Alpha (my little gatemouth wife and hip’d as she can be) had a big fine dinner ready for us,” Louis wrote. “And I’m tellin’ yoo we ate so much until we had to say forgive ‘us’ as we rose from the table.”

Later in the same letter, Louis continued: “After the dance let out which was around two in the morning – Grow and I went home where Alpha was waiting for those wet clothes that I changed at the dance-so she could pack them some place until our bus reaches the next town-then she usually puts them in a laundry…She has that routine down to the last frazzle…She even taught my routine of how to keep plenty handkerchiefs (one of the main things)-and also take good care of these fine vines..Savy?”

Thus, everything sure seemed normal on October 1, 1941, though it should be pointed out that Louis was writing to Feather not simply as a friend but in Feather’s new role as Armstrong’s press representative; alluding to Lucille or troubles with Alpha would have been bad for publicity. I do think these appearances by Alpha are blips on the radar because, in my opinion, matters had seemingly fallen apart by the time Armstrong returned to the recording studio on November 16. What is my evidence? On that date, Armstrong chose to record a sober, instrumental version of a song that was already 20 years old: “I Used to Love You (But It’s All Over Now).” Perhaps I’m reading too much into it but it seems like an out-of-left-field choice that Armstrong would have personally wanted to do, not something foisted on him by the powers that be at Decca. If you haven’t heard it, give it a listen:

Though Louis had now put his feelings into his music, according to Louis himself, he and Alpha didn’t officially meet their Waterloo until they were together in Detroit. Consulting the newspapers of the period, we find that Armstrong began a run at the Paradise Theater on December 26, 1941. By January 12, 1942, gossip columnist Walter Winchell alluded to trouble in paradise in the “melting pot” portion of his column, devoted to celebrities breaking up: “The Gene Krupas, the very social T. Balfes, the Lou Novas, the T. Dorsey vocalist (and his bride) and the Louis (Old Satch) Armstrongs (his 3rd squaw) are in The Melting Pot.”

Louis read Winchell’s column and decided to set the record straight in a letter he sent to Winchell on January 19. He references the Detroit blowup, brought about by a tipsy Alpha telling Louis that she had been cheating on him with Charlie Barnet’s white drummer, Cliff Leeman. Not only that, but Leeman had been giving Alpha money to pay her “gas bills,” which particularly rankled Louis. “Brother Winch-can you imagine my wife ‘Bragging about this Lad paying a few lousy gas bills-when I’ve been giving her THOUSANDS and ‘THOUSANDS of Dollars for ‘Furs-Diamonds, Jewelry, etc.,” he wrote. “It really ‘Kills, One Doesn’t It?” Armstrong humorously didn’t blame Leeman. “If I only could se him and tell him how much I appreciate what he’s done for me by taking that Chick away from me,” he continued. “So if you should run across him ‘Please thank him for me ‘Wilya Mr Winch?….And with all of that – I still think he is one of the greatest drummers that we have here in our-U.S.A.”

Here is a copy of the complete letter, somehow obtained and saved by Jack Bradley:

Winchell knew he had a home run and decided to print Armstrong’s letter at length immediately. He removed Leeman’s name and eliminated a few lines here or there, but this is how it appeared in his column on January 22:

Not everyone approved of Louis’s way of airing his dirty laundry. “The whole town is talking about Louis Armstrong, who shouldn’t have written Winchell that letter about a wife he once loved and vice versa,” Billy Rowe wrote in The Pittsburgh Courier on January 31.

But even Rowe took Louis’s side when his and Alpha’s drama spilled into court with Alpha filing a suit for separation, accusing Louis of “inhuman treatment, refusal to provide and abandonment.” Alpha averred that “repeated instances of infidelity have made life (with him) unbearable” and asked for alimony of $250 a week, plus $5,000 for counsel fees. Rowe got wind of this and reported, “Alpha Armstrong peeped out from one of her six fur coats in domestic court here last week to ask Louis Armstrong, her estranged hubby, for a two hundred and fifty dollar allowance per week for life as a parting gift. What would you say? Well, so did Louie!”

For reasons unknown, Alpha’s suit didn’t gain any traction and her split with Louis disappeared from the newspapers–until July 1942, when Louis filed for divorce from her. “A suit for divorce was filed Tuesday on behalf of Louis (Satchmo) Armstrong, famous trumpet player by his attorney, Lewis Bennett, against his third wife, Alpha, whom he married in Houston during October, 1938,” the Associated Negro Press reported on July 26, 1942. “Armstrong charges desertion saying his wife left him June 28, 1941, and has since refused reconciliation. The statements on which the divorce action was started were made by the orchestra leader when he played the Regal Theatre here recently.”

A petition was filed on September 15, setting the proceedings in motion. On September 25, Louis wrote to William Russell, “By the time you get this letter-I’ll have my Divorce from my third wife and I’ll be on my way to the Altar with my fourth wife…Which is the sharpest one of all of them….Yessir-Madam Lucille Wilson is gonna make all of the rest of the Mrs. Satchmo’s look sick when she walks down the Aisle with Brother Satchmo Armstrong looking just too-pretty for words with her little Brown Cute Self…Lawd today…..So you’d better (Congratulate) us right now….” On September 29, a hearing was held in Chicago in which Louis and his lawyers maintained that Alpha deserted him. “I treated her swell,” Armstrong said according to the court transcript. “I was a good husband to her.” Alpha didn’t show up to the hearing.

The trial did provide Louis with one of his favorite stories. According to notes William Russell took on a conversation with Louis in 1953, “About the Alpha divorce — went before the judge. Onah Spencer, writes for Downbeat, was my witness. He had this thing in his ear (hearing aid) and he kept saying, ‘Huh?’ So I said, ‘Judge, can I tell you about it?’ I began telling him and he asked me, ‘Have you got a cold?’ I said, ‘No, I always talk this way.’ A minute later he said, ‘Divorce granted.’”

“Louis ‘Satchmo; Armstrong, the trumpet king of swing, won a divorce from his wife, Alpha, following a court hearing here last week,” the Associated Negro Press finally reported on October 10. “The petition was filed by Armstrong’s lawyers on September 15. The famous musician and orchestra leader was granted an uncontested divorce on the grounds of desertion. His wife was reported to have been in New York City when the case was called. Reports say that the trumpet player is planning an early marriage to Miss Lucille Wilson, a New York stage beauty, who is visiting in the city. “

Indeed, Louis married Lucille Wilson almost immediately while on the road in St. Louis. I say “almost” because it seems Louis maybe hesitated a day, not wanting to be married again on October 11–his and Alpha’s anniversary. Instead, he wed Lucille on October 12 and the rest is history. Here’s Louis and Lucille cutting their wedding cake, Louis definitely showing the effects of the aforementioned “Nine Day Diet”:

Even though Louis had found lasting (with a few bumps along the way) happiness with Lucille, he never quite shook the feeling of being betrayed by Alpha’s cheating on him. Most of the adoring quotes about his and Alpha’s early courtship that we featured in part one of this series came from a series of handwritten notebooks Armstrong compiled for Belgian author Robert Goffin in 1944. At the end of his mostly positive reminisces, Armstrong’s mood turned dark.

“She had lovely Tastes for Clothes,” Louis began. “Even before I was really able to really buy her a lot of fine Clothes–Furs and Diamonds galore. She was always a young girl was very Neat and Clean–And always loved the ‘best’–you could tell that when she picked me. Then, if Alpha was going downtown to Buy a Couple of dresses and she didn’t have enough money to get Two good ones–She’d come home with that one good one. She did not have a whole lots of clothes when I met her–but what few she did have was good. And was she ‘Innocent’ my my my. To believe that Alpha turned out in later years to be a no good Bitch Why–I am Still Flabbergasted (Surprised as Ol Hell).“

At some point, Armstrong again channeled his feelings into his music, penning what eventually became known as “Someday You’ll Be Sorry” with Alpha in mind. In a 1964 interview with Fred Robbins (full audio can be found here), Armstrong recounted the tale of how he wrote it:

“Some years ago we was making some one nighters, I think when I had the big band, in East Grand Forks, North Dakota. And it was cold! We was in bed, you know, and about 4 o’clock in the morning, that song kept on running across my mind. And so I got up from a sound sleep and wrote it. It was just like a theme song in a musical play that I was supposed to be writing in my mind, you know.” When Robbins asked how he found inspiration in Grand Forks, Armstrong responded, “Well, we were under the covers! I got up and put on my robe and sit down and start writing this tune. And Lucille looked up out of the bed and said, ‘Are you all right?’ Well, that’s where it came from. It kept bugging me, you know. So finally wrote the tune and went on back to bed and the next day, there it was. And we started playing it ever since.”

In a 1991 article penned for Storyville magazine, Armstrong’s publicist Ernie Anderson continued the story:

“If you listen to the lyric of this song you will perceive instantly that it is addressed to Alpha although her name is never mentioned. Some day, you’ll be sorry. The way you treated me was wrong. There won’t be another to treat you like a brother. Some day you’ll be sorry, dear.

At that time Louis had a contract with Decca so the next time they came into Manhattan for a record date, he put the arrangement up on the music stands. The A & R man on the date said, “What’s this?” and Louis said, “Oh, that’s a new song I wrote.” Then the A & R man said, “Oh, we haven’t time for anything like that today.”

Decca managed to ignore Louis’s new song throughout his next half a dozen record dates for Decca. “Every time I’d put the music for Some Day up on the stands. Then they’d turn me down again,” Louis recalled. “Finally that arrangement was so old and worn out that it was practically transparent!”

***************

Okay, if you’ve been with me this far, you know I love to do so some detective work. Newspapers.com has a selection of Grand Forks, North Dakota newspapers so I searched for any Armstrong performances from the 1940s. According to Library of Congress records, Louis didn’t formally copyright the song until November 29, 1946, a year he seemingly didn’t step foot in North Dakota, at least according to the newspapers.

But Armstrong did perform performed at the States Ballroom in Grand Forks with his big band—on December 6, 1941. The weather? 14 degrees at 4 a.m. the next morning, so that definitely corroborates the “freezing” aspect of the story. December 1941 seems a bit early, though, as the Detroit blow-up had not yet taken place, but he had already recorded “I Used to Love You” and was clearly having issues with Alpha.

Armstrong also saved a lead sheet; the handwriting doesn’t appear to be his, but he took full credit for both music and lyrics:

Anderson’s nugget about Decca not wanting to record it is indeed interesting as Armstrong had dates with the label in April 1942, August 1944, January 1945, and January 1946, followed by RCA big band dates in April 1946, October 1946 and March 1947, before finally recording it for RCA Victor in May 1947. For reference, here’s that iconic first recording:

But long before the RCA date Armstrong did indeed have an arrangement made for it that was never recorded by his big band, though it was adapted into the backing provided by the nonet on the 1947 RCA recording. Here’s Louis’s part:

And for the musicians in the house who might be baffled by the unusual key of “D” heard on the RCA recording, it was indeed written in that key; here’s the guitar part (though, yes, it modulates into Eb midway through):

In case you’re curious, “Some Day” is arrangement 90-C in the big band book; 91-C was “I Left My Sugar in Salt Like City,” written in 1942 and broadcast by Armstrong in 1943, and 95-C was “Going My Way,” written in 1944 and performed by Armstrong that same year. Going backwards, 89-C was “As Time Goes By,” which exploded in popularity in 1942 and was broadcast by Armstrong in either late 1942 or early 1943. This, to me, is proof that an early 1940s date for the composition and arrangement of “Some Day” makes sense, potentially composed in December 1941, arranged sometime in 1942 or 1943, copyrighted in 1946, rejected by both Decca and RCA during Armstrong’s 1942-1946 sessions, and finally recorded by the nonet in May 1947.

(Though just to put a punctuation mark on “Some Day,” I’m not the first person to point out the similarities between Armstrong’s composition and “Good Night Angel,” a pop tune composed for the 1938 film Radio City Revels Allie Wrubel and Herb Magidson and recorded by several artists in that time, including Artie Shaw, Al Bowlly, and more. It’s quite possible the melody invaded Armstrong’s subconscious while he was somnolent in Grand Forks and he woke up believing he composed an original masterpiece–though any coincidences were finally removed in 1957 when Milt Gabler had Louis himself record “Good Night Angel” for the album Louis and the Angels.)

That’s the saga of “Some Day”–but what of the saga of Alpha Smith? After her divorce with Louis, she seems to have settled on the west coast to lead a quiet life. She doesn’t appear in the press until an article from September 15, 1945–coincidentally about Louis separating from fourth wife Lucille! It appears Lucille must have thought she could tame Louis’s adulterous ways and threatened to leave when she found out she couldn’t. They soon reconciled and Lucille learned to do what she had to do to maintain a successful marriage to someone like Louis.

But in that September 1945 article is this passage: “Alpha Smith, another chorus girl, became the third Mrs. Armstrong in a ceremony performed at Houston, Texas, in [1938]. Mrs. Alpha Armstrong lives in Los Angeles. The mother of the 3rd Mrs. Armstrong has had the keeping of the adopted son of Armstrong, Clarence Armstrong, before and since the wedding of her daughter.”

Indeed, as noted in this post, Clarence continued to live with Alpha’s mother, Florence Smith, in Chicago until her passing in 1953. We’ve previously shared numerous photos of Clarence and Louis reuniting in Chicago in the 1940s and early 1950s so it’s safe to assume that Louis regularly saw Mrs. Smith and even sent her money to take care of Clarence.

Which brings us to Louis’s bizarre quote from the 1954 Ebony article, “Why I Like Dark Women”: My divorce from Alpha didn’t end my friendship with her family. After she died I took care of her mother for a number of years. It was a pleasure to help her because she was such a wonderful old lady. I did it too out of respect for Alpha’s memory and the years we were together.”

For years, that led many Armstrong historians to assume, as Terry Teachout did in his book Pops, that Alpha passed away shortly after their divorce, perhaps a victim to the “three tumors” that felled her in 1939. But no, recent research has turned up multiple death notices for Alpha–in January 1960. Here’s one from the Los Angeles Citizen News of January 6, 1960:

And that’s really all that’s known about Alpha in the years after her divorce with Louis. I’ve searched Newspapers.com, I’ve searched Ancestry.com, I’ve searched ProQuest’s Historic Black Newspapers database; no mentions, not even an entry in the 1950 census. She was in Los Angeles in 1945 and died in Beverly Hills so she must have liked California but what did she do for a living? Did Louis continue to send her money? Did they keep in touch at all?

The answer seems unlikely. Louis had positive reunions with both his first wife Daisy Parker and second wife Lillian Hardin after their divorces and made a point of saying in multiple interviews that he remained “the best of friends” with all of his ex-wives. But there’s not a trace of evidence that he kept in touch with Alpha after they separated. No letters, no photos, no nothing. She’s rarely a topic of conversation on Louis’s tapes and when she does pop up on one tape from the 1950s, it’s because of a mention of Walter Winchell. Louis reminisces about Winchell, mentions the time he wrote him about his troubles with Alpha, then gets a bit worked up, almost mentioning Cliff Leeman, talking about him paying Alpha’s gas bills, and getting a bit tongue-tied before he changes the subject. Here’s the audio:

And that’s it–that and the “Majestic Face” story we already shared in a previous post, which Louis did tell on an episode of The Tonight Show in 1970. It’s clear that Alpha left scars and Louis didn’t exactly relish the idea of going down memory lane when it came to the many years they spent together. At the same time, he saved everything, including Alpha’s scrapbook and the dozens of snapshots he personally numbered with green ink. Louis’s late 1960s clarinetist Joe Muranyi told me that Alpha once came up in conversation and Louis had a wistful look as he talked. “It was clear that he had a lot of fun with Alpha,” Joe surmised.

Hopefully some of that fun–and heartbreak–has come across in this five-part series. If anyone else has anything to share on Louis and Alpha, please leave a comment. The introduction of those early photos on the road with Lucille have given us to idea to delve a little deeper into her early years so be sure to come back soon as we start a brand new series on the fourth–and final–Mrs. Armstrong.