50 Years of “Louis Armstrong and His Friends” Part 3: The May 27, 1970 Session

In Part 1 of our look at the album Louis Armstrong and His Friends, we examined how Louis Armstrong prepared for this work after consulting with producer Bob Thiele when Thiele visited him at his home in Queens. Part 2 focused on the events of May 26, 1970, which kicked off with an all-star assemblage gathered to celebrate Armstrong’s impending 70th birthday before Armstrong got down to business and recorded four Oliver Nelson arrangements. It was quite a day in the studio and we are fortunate that Jack Bradley was there with his camera to document all of it.

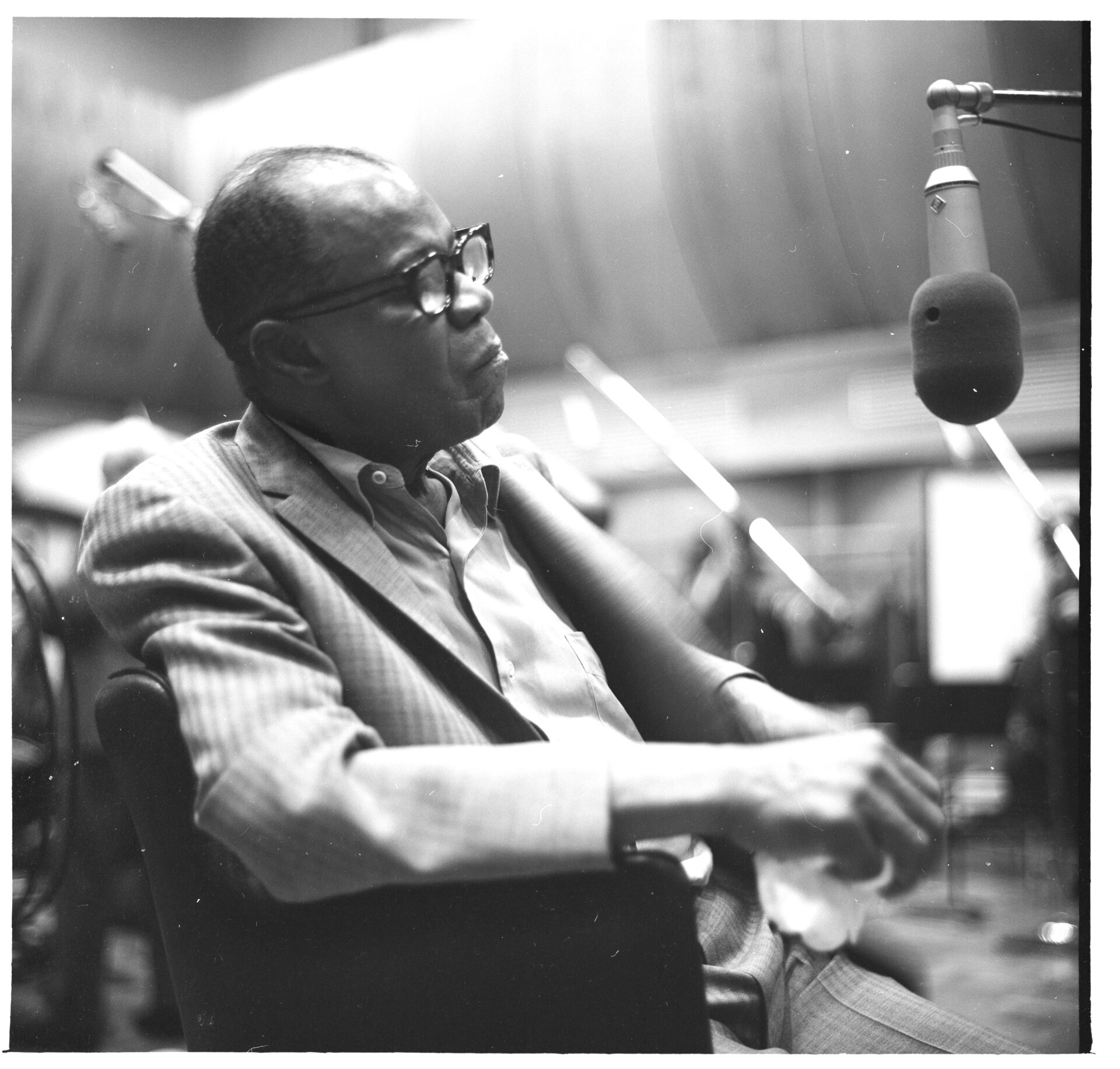

Unfortunately, when Louis returned to RCA studios the following evening, May 27, for the album’s second session, Bradley was unable to attend. Thus, we don’t have any photos to share from that date, but we do have the music and the Oliver Nelson arrangements. Also, the personnel didn’t change (except for the addition of Gene Golden on congas) and the location remained the same so here is another unpublished Bradley photo from the May 26 session to set the scene.

The May 27 session began with a brand new composition by George David Weiss, Pauline Rivelli and Thiele, “His Father Wore Long Hair.” In part 1 of this series, we shared Louis’s lead sheet, as well as a demo recording he used to learn the tune. When Thiele visited Armstrong at home in March 1970, he recalled that they spent a lot of time talking about Martin Luther King Jr. and religion. “Louis said that when he was sick in the hospital, he knew he was near death and he talked to God,” Thiele said at the time. “Louis is very sincere about this. He sincerely believes a lot of trouble in the world today is because people don’t take the trouble to talk to God.”

Clearly Thiele was trying to tap into that side of Armstrong with “His Father Wore Long Hair.” Like much of the album, the lyrics commented on contemporary society, reminding listeners that even Jesus’s hippy-ish parents were “condemned” and “scorned,” finally asking, “Sweet Jesus, Jesus, what would you say? Is the world any different today?” It’s an admirable message and Armstrong delivers it with all of his heart but the result is, in the opinion of this writer, the weakest track on the album and one of the more dated and forgettable entries in the Armstrong discography. Listen to it here:

Next up was “Everybody’s Talkin’ (Echoes),” written by Fred Neil and memorably performed by Harry Nilsson in the 1969 film Midnight Cowboy. Louis listened to Nilsson’s version repeated times at home before coming to the studio. Once there, he nailed the vocal, backed by a wonderful, contemporary-sounding Oliver Nelson arrangement that would have been right at home on the Top 40 radio of the day. The band cooks, too, especially Bernard “Pretty” Purdie on drums, James Spaulding on flute, Frank Owens on piano and the numerous bass players.

We might not have a photo, but we do have the full Nelson arrangement. Here is Louis’s complete part:

Notice the simple vamp at the end and listen to what Louis does with it, singing the written line three different ways before improvising some spoken asides, all punctuated with that gigantic, genuine laugh of his. This recording also gives a great insight into what Louis could have done if he lived another decade, seamlessly fitting in with the Motown/R&B sounds of the 1970s just as he had fit in with every development in pop music since the 1920s. Listen here:

Finally, it was time to tackle “The Creator Has a Master Plan,” another song connected to Bob Thiele, who produced Pharaoh Sanders’s 1969 album Karma for Impulse Records. That album featured a meditative 32-minute performance of “The Creator Has a Master Plan” that was edited down to become a surprising radio hit for the free jazz saxophonist thanks to the lyrics and a Pygmy-styled, yodeling vocal by Leon Thomas.

Thiele invited Thomas to the Louis Armstrong and His Friends sessions (he’s in photos from the May 26 date), plus flutist James Spaulding was in the orchestra to recreate his role on the original hit. Armstrong prepared by listening to the Thomas recording and Nelson wrote the arrangement, similar to the original but with layers of moody strings. Here’s Nelson laying out the arrangement the day before:

As can be glimpsed in the photo above, each part had “LOUIS ARMSTRONG” stamped in the upper right corner–except the vocal part, which doesn’t mention Louis at all. Here’s the first page:

As you can see, neither Armstrong or Oliver Nelson’s name appears on the part; their names are on every other part. This is worth noting because of the mystery surrounding the track: in the studio on May 27, Armstrong sang from start to finish all by himself. But on the finished record, it appears as a duet with Leon Thomas. Thomas’s part was clearly overdubbed later but was that always the plan? It doesn’t seem that way.

First, listen to the finished track with Thomas and Armstrong swapping lines:

In 2002, RCA revived its Bluebird label and produced a series of CD reissues, including some Flying Dutchman material such as Louis Armstrong and His Friends. For the reissue, Bluebird included the full master take as it went down on the studio on May 27–and it’s Louis singing the entire piece from start to finish, not even leaving any holes for Thomas to overdub his part. Not only that, but James Spaulding’s “out” flute playing in the beginning is also absent; perhaps Thiele felt that Armstrong’s ears, which by then accepted much modern jazz but really nothing remotely avant-garde, wouldn’t approve.

Regardless, the unedited take with just Armstrong is a fascinating document. Admittedly, he does not sound very comfortable on the verse, singing with feeling but for one of the only times in his career, not hitting some of the notes entirely on pitch. He eventually gets to the title phrase but sounds a little bored chanting it over and over. Eventually, though, the band digs in on the vamp (Nelson wrote on the flute part “Start To Get Into It”) and Louis leaves the music behind and does what he does best: improvises around the melody, teases it (those “oy-yoy-yoy-yoys” break him up), calls our attention to the “cats” swinging and “chops is flying all over the studio,” points out Pretty Purdie’s resemblance to Count Basie and scats with joy, playing with the title phrase until the closing fade.

Thiele must have felt that Armstrong’s impishness at the end undercut the message of the song so all the “fun” was cut out of the master recording. And considering that Armstrong still wasn’t very comfortable with the verse, it made sense to get Thomas to sing it in his iconic fashion, even though it’s still a mystery if that was always the intention.

Unfortunately, the Bluebird CD is no longer in print, though it’s still available on Amazon. Ace Records bought the Flying Dutchman catalog and their reissue of Louis Armstrong and His Friends only contains the master takes and no bonuses. But thanks to the magic of YouTube, the unedited, all-Louis take of “The Creator Has a Master Plan” is still up for us to share:

Without any first-hand stories or photos from the May 27 date, we can only assume that it was a tough one and that these three selections took a long time to record since most dates aimed to produce four sides. Also, in part one, we discussed Erroll Garner’s “Dreamy,” which was retitled “Have I Gone Dreamy” and outfitted with new lyrics by George David Weiss. Nelson wrote a full arrangement specifically for the string-heavy instrumentation on the May 26 and May 27 dates but there was not enough time to record it–or quite possibly Louis didn’t feel comfortable with the extra wordy lyrics. We’ll never know, but we do still have the full arrangement in our Archives; here’s Armstrong’s part. (Can’t help imagining how nice it would have been to have an Armstrong recording of this instead of “His Father Wore Long Hair” or “Here is My Heart for Christmas” but alas….)

Louis was able to take a break on May 28 but he’d be back in the studio on May 29 to record the final four selections for the album (though Nelson again would bring an extra arrangement to the session that would go unrecorded). The band would be packed with jazz greats and a choir, the studio would be filled with guests and friends and Jack Bradley would be back with his camera. Come back on Monday for the final part of our look at Louis Armstrong and His Friends.