“Armstrong’s Personal Recordings”: Louis Armstrong Final Tapes Part 1

Back in March, we posted an extended piece about the 50th anniversary of Louis Armstrong’s final public performances at the Waldorf-Astoria. If you know your Armstrong history, you most likely know that July 6 will represent the 50th anniversary of Louis Armstrong’s passing.

But what happened in between the Waldorf engagement and Pops’s last breaths? A lot. Two days after taking his last bows onstage, Armstrong was felled by a major heart attack and sent to Beth Israel Hospital, where he needed an emergency tracheotomy to survive. He fought for his life in the ensuing weeks, the media filled with stories of Armstrong bouncing between stable and critical condition; here’s an Associated Press story saved by Lucille Armstrong:

Armstrong was finally released from the hospital on May 8. His legs still unsteady, Lucille had an electric stair chair installed to help him get to the second floor of their Corona, Queens home:

Lucille related that Louis stubbornly refused to use a cane at first, resulting in a fall that most likely necessitated the Band Aid spotted on his knee in this photo:

In late May, Armstrong felt strong enough to welcome New York City Real Estate Commissioner Ian Duchan to receive the deed of the abandoned property next door to his home, recently purchased by Louis and Lucille. “I’m going to landscape this lot with trees, bushes and flowers and maybe even a small croquet court,” he told reporters. “Then, I’m just going to sit out there and enjoy my garden and maybe even blow my horn a little.”

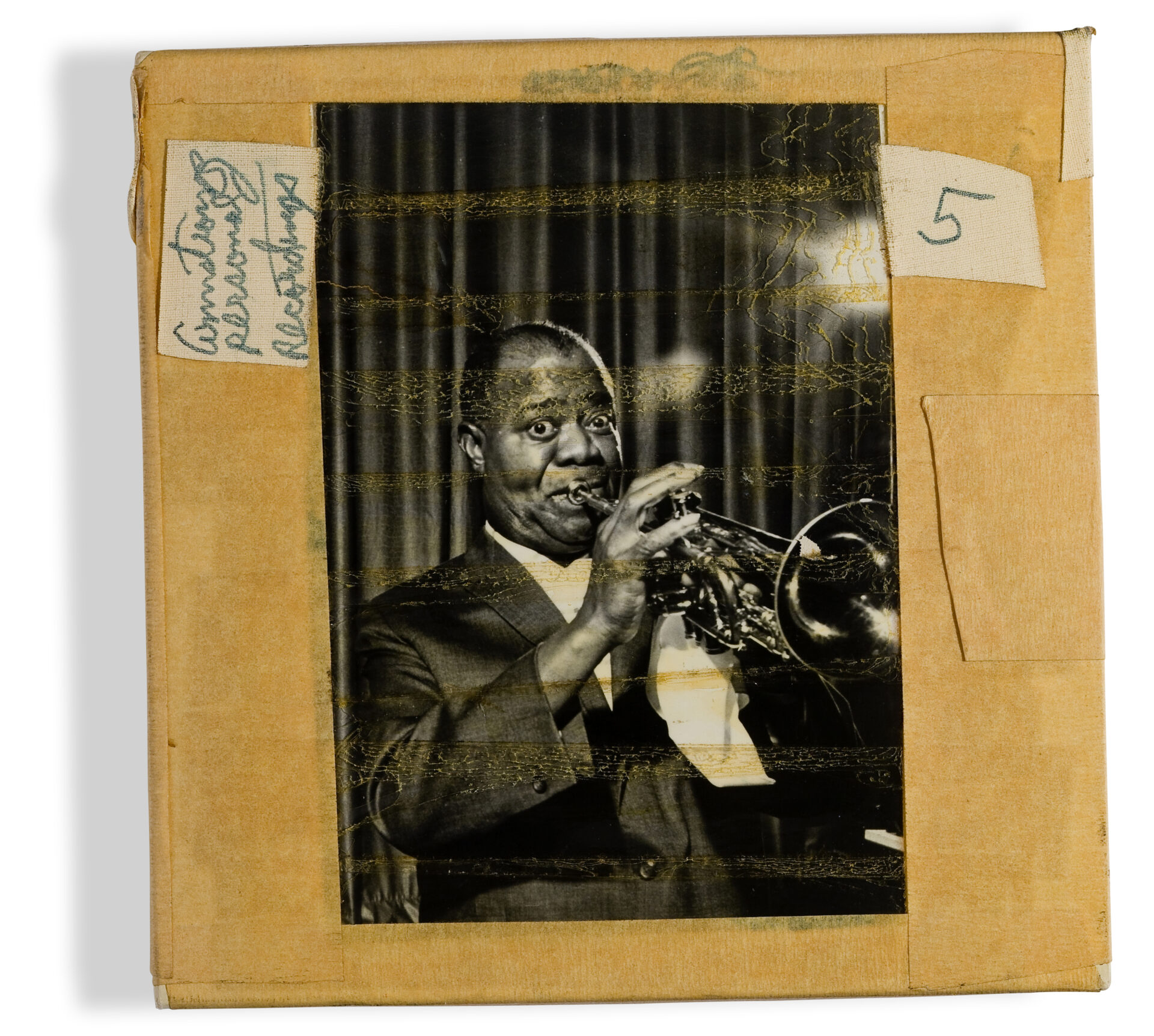

Armstrong grabbed a copy of the May 27 issue of the New York Daily News and cut out the article about his new property and turned it into one of his tape box collages:

On the flip side, he cut out photos of himself, his trumpet, and Fats Waller’s manager Ed Kirkeby from the May 1971 issue of Jazz Journal to make another collage:

Interestingly, the tape contained in that box remained blank. But the fact that Armstrong was making collages illustrates that he was feeling well enough to resume his favorite at-home hobby: making reel-to-reel tapes.

Last year, we devoted ten posts on this site to chronicling the first 50 tapes Louis Armstrong made after his release from intensive care in Beth Israel in June 1969. (It’s been a crazy year but we’ll resume that series eventually, hopefully in the Fall!) Armstrong started with “Reel 1” and had reached “Reel 170” by the time of the Waldorf gig.

Now, back home for the foreseeable future, Armstrong turned his attention to his tapes. Instead of continuing his 1969 series, Armstrong decided to start again from scratch but this time with a new goal in mind: he only wanted to hear his own records.

There’s something extremely touching about this new series, arguably the most influential musical genius of the 20th century spending his final weeks listening to nothing but the music he created. But Armstrong also had an ulterior motive; trumpeter Chris Clifton visited in late June and said that Armstrong was playing along with everything he was taping, specifically mentioning his 1954 recording of “Trees,” a record that didn’t even feature any trumpet work. Jack Bradley was along for that trip and took this photo of Louis playing trumpet in his den while listening to his recordings:

Unfortunately, Armstrong now made his tapes through direct input, his Tandberg tape decks picking up only the sound from his turntable and none of the sounds of Armstrong’s den. Thus, unlike the treasures from the 1950s, Armstrong’s 1971 tapes don’t feature any sounds of conversations, practicing, phone calls; Armstrong doesn’t even play disc jockey and introduce the recordings.

But between late May and his death on July 6, Armstrong made nearly 20 tapes in the series he dubbed “Armstrong’s Personal Recordings.” I realize this has been quite a preamble but it’s all been to set the stage for what will be a weekly series between now and July 6, focusing on the music Louis Armstrong listened to–and the collages he made–in his final days. Because almost all of his recorded output is in print in one way or another, it’s possible to create playlists and listen along just as he did.

Thus, we start with “Armstrong Personal Recordings 1,” which did not feature a collage on the front or back of the box. Here’s the front:

And the back, which has the number:

Each of the tapes in the series feature a handwritten listing of the contents of the tape, written by Armstrong himself. Note, too, that Armstrong was using a black marker to make his track listings and his handwriting even looks more fragile than ever before. We’ll be sharing each one, starting with the playlist for volume 1:

What a wild mix, opening with the 1964 Hello, Dolly! album, jumping to a 1966 single of “When the Saints Go Marching In,” followed by the 1971 Brunswick album Greatest Hits Recorded Live (selections from a 1968 BBC date and the only album produced by Pops), his bizarre 1970 final studio album Louis “Country and Western” Armstrong, and finally, a compilation of his landmark 1928 recordings made with Earl “Fatha” Hines, V. S. O. P. (Very Special Old Phonography).

“Armstrong Personal Recording” Reel 2 also didn’t have a collage:

As for the content sheets, something is awry. Only two pages survive and on the top of what Armstrong labeled as the first page, he crossed something out on the top and wrote “Armstrong Continues.” Upon playing this reel, it actually opens with the second half of the aforementioned V. S. O. P. album, containing a number of 1928 classics not notated in Armstrong’s list: “Weather Bird,” “Fireworks,” “Skip the Gutter,” “Our Monday Date,” “Don’t Jive Me,” “West End Blues,” “Sugar Foot Strut,” “Two Deuces,” and “Squeeze Me.”

(A touching side note: Armstrong most likely made an extra copy for his old pal, drummer Zutty Singleton, still ailing after suffering a stroke in 1969. After Armstrong died, Singleton was interviewed by journalist Patrick Scott, who reported that Zutty “never lost touch with Armstrong, who spent much of the last two weeks of his life compiling a tape of all the recordings he and Singleton had made together, notating in his own faltering band the date and personnel of each. ‘That was the real Louis,’ Singleton said yesterday, ‘Going to all that trouble because he knew it would cheer me up—even though he also knew he was dying himself, and don’t let anybody tell you he didn’t.)

After that, Armstrong dubbed what appears to be a dub of the CBS LP Louis Armstrong Sidney Bechet Clarence Williams Blue Five….except every copy in our Archives is copyrighted 1973. Hmmmm. Could CBS have sent him a test pressing or did it come out in an earlier pressing? Louis didn’t leave a copy behind, but he dubbed the same contents to “Reel 170” just before the Waldorf gig, and wrote the title in the corner “Louis Armstrong Sidney Bechet Clarence Williams Blue Five” so clearly he had some iteration of the record. For those who don’t know it, it contains the following: “Kansas City Man Blues,” “Wild Cat Blues,” “New Orleans Hop Scop Blues,” “Oh Daddy,” “Pickin’ on Your Baby,” “You’ve Got the Right Key, But the Wrong Keyhole,” “Texas Moaner Blues,” “Cake Walking Babies from Home,” “Everybody Loves My Baby,” “Mandy, Make Up Your Mind,” “I’m a Little Blackbird Looking for a Bluebird,” “Papa De Da Da,” and “Wait Till You See My Baby Do the Charleston.”

That LP actually ended with “Coal Cart Blues,” which is where Louis’s sheet begins. From there, Armstrong grabbed his copy of the 1968 Decca compilation, “Young Louis: ‘The Side Man’ (1924-1927),” featuring more early recordings of Louis with Fletcher Henderson, Perry Bradford, Erskine Tate, Jimmy Bertrand, Lil’s Hot Shots, and Johnny Dodds. On tape Armstrong dubbed in order but while writing his contents sheet, he got sidetracked a bit in the middle. Here’s Armstrong’s two surviving pages with explanations to follow:

On the first page, after “I Ain’t Gonna Play No Second Fiddle,” Louis draws a line and then lists a Voice of America broadcast containing a tribute that was held for Armstrong at the Waldorf in November 1970. The VOA or host Willis Conover himself must have sent Louis a copy of the broadcast. Armstrong was probably hazy as he wrote the address on the tape, turning “United States Information Agency” into “United States Motion Agency”! Armstrong also gives a hint of when it was broadcast–the 25th of some month in 1971–but doesn’t list the month; the actual tribute was November 8, 1970. The broadcast does appear on the tape but not until after the Young Louis LP concluded, after “Melancholy.”

Then another mystery: “P. Pletcher Montague – Mich 47437 Music Tape for Satchmo’s Listnings.” Armstrong was friends with both trumpeter Stew Pletcher and his son, cornetist Tom Pletcher, who indeed hailed from Montague, Michigan. The “P.” is probably another mistake, but the “Music Tape for Satchmo’s Listnings” makes it appear that Pletcher sent Armstrong something to listen to and Louis was now going to dub it to tape.

But what did he send? Finally, the answer can be discovered by looking at the note on the bottom of page 2: “A Guest Trumpet player plays Beautiful and entertain Louis Armstrong.” Louis was a wonderful writer so I’m assuming a medicated, sick haze produced the fogginess of these early writings. But I did find the original tape that Armstrong dubbed it from and it features an unidentified voice at the start explaining, “I just got back from Australia and heard this jazz band and they were great. The trumpet player is Bob Barnard and I thought he captured your 1920s and 1930s playing, etc.” The unidentified voice must be one of the Pletchers and sure enough the real ends with four fabulous recordings–“Who’sit,” “Put ‘Em Down Blues,” “Ev’ntide” and “I’m in the Market for You”–featuring Australian band led by Les Barnard and featuring the great Bob Barnard on trumpet. Bob is still with us and when told that Louis was “entertained” by his playing in the final weeks of his life, responded that it “floored” him.

Onto volume 3, still no collages in sight:

Picking up on my earlier note about Armstrong making tapes for Zutty Singleton in this period, it’s quite possible that this was another one as it opens with more from the V. S. O. P. series, containing Armstrong recordings made between 1928-1929; Singleton is on 11 of them. After that, still perhaps with other issues capturing his attention–or maybe he just liked them–Armstrong filled up the rest of the reel with dubs of Louis Armstrong Greatest Hits Recorded Live and Hello, Dolly!, repeated from tape 1, capped by a dub of Disney Songs the Satchmo Way. Here are his handwritten notes. I’m not a handwriting expert, but his writing really appears weakened on the second page (but I do get a kick out of the formal reference to “David Crockett” on the last page!):

Volume 4, now called “Armstrong Personal Records,” follows the same format as the others up to this point. Here’s the front and back:

This is the only tape of the series that does not have a corresponding set of handwritten notes so we’ll have to describe the contents ourselves. Opening with Porgy and Bess with Ella Fitzgerald, it then featured something a little different: Lil Hardin Armstrong’s spoken word record from the 1950s, Satchmo and Me. Louis and Lil had a falling out in the mid-50s; in a 1965 profile in a Toronto newspaper, Lil mentioned that he hadn’t talked to her in about a decade. In a manuscript Louis started writing in his hospital bed in 1969, he blasted her for her “corny” piano playing. Back home, he transferred a copy of Satchmo and Me early in his re-indexing of tapes. Hearing the way Lil talked about him must have really softened him up, because when Max Jones sent Louis some questions about Lil for a forthcoming biography, Louis answered them in August 1970 by praising Lil up and down for the way she pushed him. I really think Satchmo and Me melted the ice between them and it’s no surprise that he wanted to add it to his “Personal Recordings.”

Then, after two 1950 Decca goodies, “That’s for Me” and “Fine and Dandy,” Louis switched moods and dubbed Hello, Dolly! again…for the third time in four tapes! It must have really brought back some memories that he wanted to relive.

He ran out of room before it concluded so we pick it up on reel 5, the first one featuring a collage, made up from the front and back of a 1960s Salvation Army publicity photo of Louis:

As mentioned, the reel opens with the conclusion of the Hello, Dolly! LP and another full dub of Disney Songs the Satchmo Way. Here’s page one of Louis’s notes:

If the repeated albums are getting a bit exhausting, Armstrong throws us a curveball with his next selection: an unissued (at the time), complete All Stars set from a night in Sparks, Nevada in June 1964! Armstrong doesn’t even give us any hints of who recorded it (he wasn’t taping his shows any more in this period so this was clearly given to him). The good news is the good folks at Dot Time Records finally issued this complete set in 2019 so you can head to any streaming platform or purchase it direct from Dot Time here! Here’s Louis:

The third page opens with his 1969 single of “We Have All the Time in the World” and “Pretty Little Missy,” each one repeated twice. Armstrong’s method of repeating a song on tape at this stage in his career was usually to help memorize a song before performing it. Both of these songs were in his repertoire at the end so maybe he was re-familiarizing himself with both to make sure he still had them down if he did end up back onstage or on television at some point.

Next, Armstrong included two more Bob Barnard’s selections, “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea” and “Who’sit,” now describing them as “All of Louis’s tunes played by a good Trumpeter + Band.” After another repeat of Willis Conover’s Voice of America broadcast of Armstrong’s November 1970 tribute at the Waldorf, Armstrong dubbed the soundtrack to his June 1970 TV appearance on CBS’s Dial M for Music, hosted by Father Norman O’Connor and featuring the first reunion of the All Stars since Armstrong got sick in September 1968.

The next page opens with a listing for Armstrong’s March 1, 1971 appearance on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, audio of which can be heard in our aforementioned piece on Armstrong’s final engagement at the Waldorf.

From there, Armstrong dubbed a single from the French Jazz Odyssey label ostensibly sent to him by friends Hugues Panassie, Madeleine Gautier or Louis Panassie. Louis Panassie visited Louis at home in 1969 while filming L’Adventure du Jazz. This single contains Memphis Slim singing “Beer Drinking Woman”–with Gautier translating (she also translated Armstrong’s autobiography into French–and Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s “I Shall Not Be Moved.”

Already departing a bit from the “Armstrong’s Personal Recordings” theme, Armstrong goes all the way with his next selection, Pearl Bailey’s 1971 RCA album, Pearl’s Pearls. The text on the top of the LP reads “The Leading Lady of ABC TV’s Pearl Bailey Show”; Armstrong appeared on the premiere of that show in January 1971 so one wonders if this was sent to him for appearing on the show or if it was a “get-well” gift from Bailey, who became a somewhat regular duet partner in the last year or two of his life. Here are the last two pages of Armstrong’s notes, comprised of all of the above:

With that gigantic “S’all” (“that’s all”), that takes care of the first five of the series. Not to get too repetitive, but one does sense Armstrong in some duress in these early volumes, repeating a lot of the same albums, his handwriting weak, his notes full of more typos than ever. But with the collage on volume 5, Armstrong seems to have regained some of his old spirit, something that would last until the end of the series. We’ll continue telling the story next Monday.