“My Whole Life, My Whole Soul, My Whole Spirit Is To Blow That Horn”: 50 Years of Louis Armstrong at the Waldorf

50 years ago tonight, on March 1, 1971, Louis Armstrong was a guest on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. Armstrong had appeared on The Tonight Show numerous times over the years but the goal for this appearance was to promote his two-week engagement at the Waldorf-Astoria, commencing on March 2. Armstrong began his appearance by performing his own composition “Pretty Little Missy.” Midway through, he led the All Stars in an instrumental half-chorus, showing them the way with his trumpet playing.

No one could have known it at the time, but as of this writing 50 years later, it remains the last surviving sounds of we have on Louis Armstrong’s trumpet.

The backstory of the Waldorf gig is ultimately a sad one, but also a triumphant one, a somewhat heroic ending for a musician determined to go out on his shield.

In September 1968, Armstrong visited Dr. Gary Zucker’s office, suffering from heart failure and a kidney ailment. He ended up in intensive care twice over the next several months. Upon returning home in May 1969, Dr. Zucker told him it was time to retire. Armstrong stayed home the rest of the year, though he continued to play the trumpet every day, just in case he made a miraculous recovery.

By January 1970, he felt well enough to start appearing regularly on TV. He brought along his trumpet to his first appearance on The Dick Cavett Show, but ran out of gas quickly, and struggled to make it through his two performances. Even the media made a note that he should never play again after witnessing that display.

Armstrong heeded their warning and spent the next eight months regularly appearing on The David Frost Show, The Mike Douglas Show, The Merv Griffin Show, The Tonight Show, and Cavett, all sans trumpet. But by August 1970, he felt strong enough to invite Dr. Zucker to his home to attend a rehearsal in his living room with some members of his small group, the All Stars. According to clarinetist Joe Muranyi, Armstrong blew “like a man possessed.” In the end, Zucker examined him and gave him the green light to go back to performing with his trumpet again.

Armstrong knew the days of endless one-nighters were over but he couldn’t wait to make his come back in Las Vegas in September 1970, sharing the bill with Pearl Bailey. Standing ovations ended every performance. In October 1970, Armstrong blew beautifully on The Johnny Cash Show and even traveled to London for a one-night performance in front of the royal family at the Palladium.

After taking November off to rest, Armstrong returned to Vegas in late December 1970 for an engagement that lasted into early 1971. On December 30, Armstrong wrote to Dr. Zucker, breaking the ice with a joke before mentioning “shortening of my breath”:

Clearly, it was a warning sign but Armstrong paid no mind. At the end of January, his office, Associated Booking Corporation (Joe Glaser had died in 1969 but ABC still booked Armstrong) received an offer: two weeks at the Empire Room of the Waldorf-Astoria, two shows a night, five-nights a week, $15,000 per week (about $97,000 a week in 2021 money). Armstrong accepted. Here’s his copy of the contract, signed on January 18, 1971:

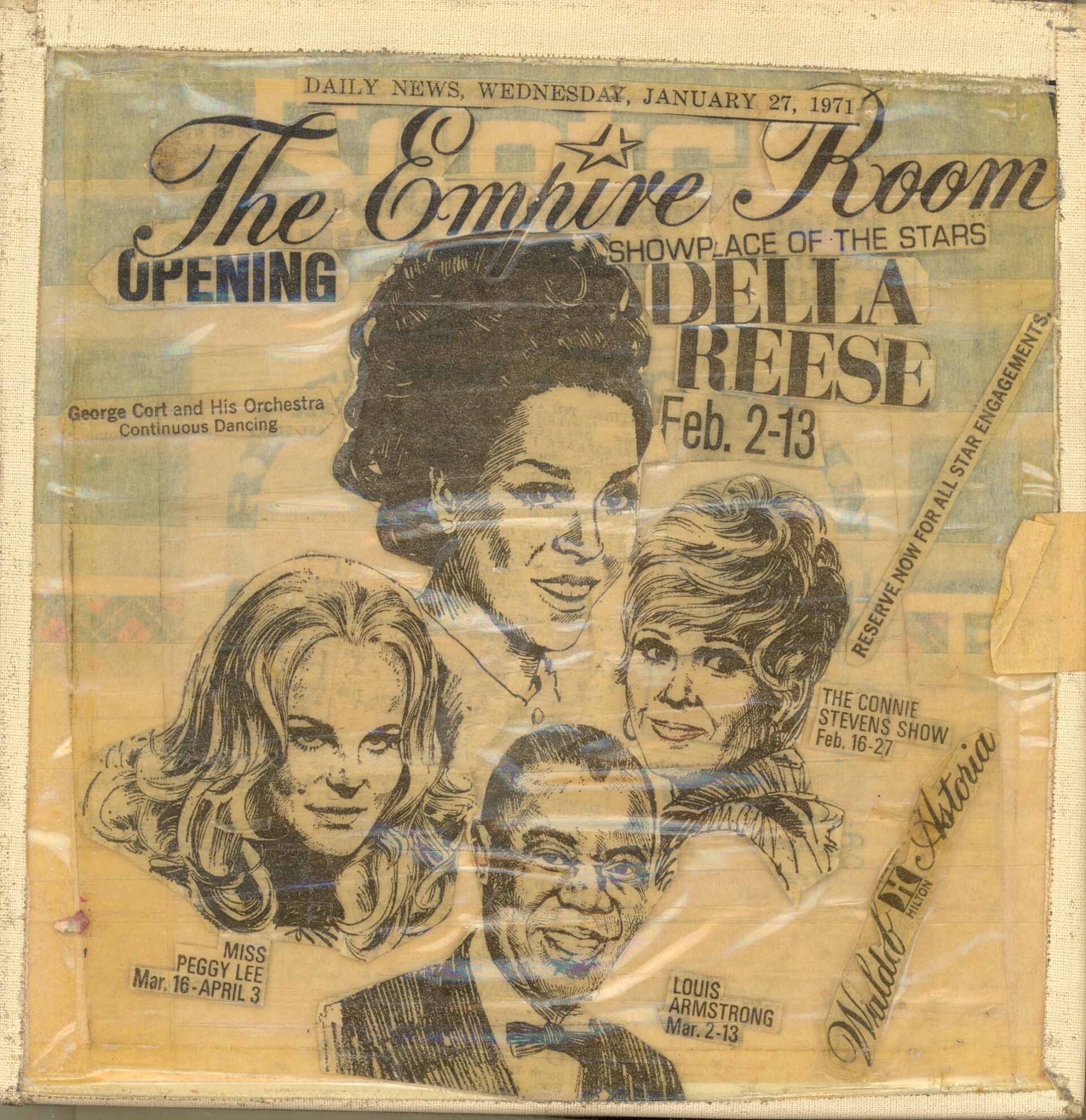

One week later, the New York Daily News began featuring Armstrong in a Waldorf advertisement. Back home in Corona, Armstrong cut out the ad and Scotch-taped it to the front of one of his tape boxes:

Shortness of breath aside, Armstrong must have felt invigorated to get back to a taste of his old way of life. The day after that Waldorf ad was published, Louis and Lucille traveled to Washington D. C. along with trombonist Tyree Glenn for a performance at the National Press Club on January 29, 1971. This recording was eventually issued on LP and CD and features one of Armstrong’s final strong solos on “Hello, Dolly” (he even quotes “I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say”):

Two days later, on January 31, Armstrong appeared at the 20th Annual United Cerebral Palsy Telethon. No video or audio has survived (or has it? Someone, check your attics!), but Jack Bradley was watching and in his Coda magazine column, noted that Armstrong played even stronger than he was sounding before he first got sick in 1968.

On February 10, it was off to the David Frost Show, a beautiful appearance that included a little bit of trumpet playing on “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” and “That’s My Desire.” Fortunately, this performance has turned up on YouTube:

Armstrong doesn’t play much trumpet on that broadcast and what’s there is a bit on the shaky side. It’s probable that his health was once again worsening. According to Lucille Armstrong’s date book, which survives in our Archives, Louis had his regular monthly check-up with Dr. Zucker the next day, February 11, at noon. According to Zucker, Armstrong was gasping for breath. “Louie, you could drop dead while you’re performing,” Zucker later recounted to James Lincoln Collier. Armstrong responded, “Doc, it’s all right, I don’t care.” Zucker continued:

“He did a very interesting thing. He got into this transported state. Sitting there on the examining table he said, ‘Doc, you don’t understand,’ he said. ‘My whole life, my whole soul, my whole spirit is to blooow that hooorn.’ And he sat there for a moment sort of removed and went through the motions of blowing that horn. ‘I’ve got booking arranged and the people are waiting for me. I got to do it, Doc, I got to do it.”

In 1996, Zucker sat down for an interview with Michael Cogswell, Director of the Louis Armstrong House and Archives, and talked more about this visit and about what he negotiated to allow Armstrong to perform the Waldorf engagement:

Unable to persuade Armstrong to cancel the gig, Armstrong was free to go on national television to start promoting it. On February 21, Armstrong wrote to clarinetist Slim Evans, “Your boy Satchmo is getting pretty sassy these days. Blowing his black ass off. I knew I could, all the time. My fans and friends, quite naturally they’d be a little uneasy about things, but as for me, they’re my chops. I wear them 24 hours a day, and I keep them in good trim.” The very next night, he appeared on The Dick Cavett Show and opened with a demanding instrumental, “Ole Miss.” Almost as if to prove a point, Armstrong even took a solo in the middle, something he didn’t even do when he regularly performed the number in the late 1950s and early 1960s. For those expecting the earlier powerhouse, you won’t find it in this clip but as to Bradley’s earlier comment, it is actually stronger than some of his late 1960s work:

Finally, we get to the whole reason for today’s post. On February 28, Armstrong began rehearsing with the Waldorf’s studio band, who would join him for the two closing numbers, “What a Wonderful World” and “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South.” He reunited his All Stars with clarinetist Joe Muranyi, trombonist Tyree Glenn, pianist Marty Napoleon, drummer Danny Barcelona and on bass for the first time since 1965, Arvell Shaw.

The following day, after another rehearsal, Armstrong showed up at Johnny Carson’s studio at 3 p.m. with the All Stars for an appearance on The Tonight Show. Armstrong opened with “Pretty Little Missy” and that aforementioned trumpet spot, still sounding quite strong considering this was so close to the end. He then made his way over to the couch and though the video does not survive for this show (Carson didn’t retain control over his Archives until 1972; only a small, random selection of shows survive from the first ten years of The Tonight Show), he sure sounds like he’s in a great mood on the couch, talking about the Karnofsky family, his first horn, his new album, the Waldorf and more. After the commercial, Armstrong and the All Stars jump “Blueberry Hill” at a faster clip than usual, swinging until the end.

After the broadcast, Armstrong received a reel-to-reel tape of the entire broadcast (also on the bill was the great comedian Albert Brooks and actress Sue Ann Langdon). At some point back home, he covered the box with photos of him and Lucille kissing over the years on the front, and a photo of him being carried in Leopoldville in 1960 on the back:

And now, 50 years later, here is the complete audio from Louis Armstrong’s segments (with a subtle watermarked beep to prevent commercialization or other uses without permission), including the last sounds we have of his trumpet:

One night later, Armstrong began his engagement at the Waldorf-Astoria. What happened next has been the subject of many different tellings. Arvell Shaw told it with tears in his eyes because to him, Armstrong was in dire shape and needed help walking out to the stage. Shaw was last with Armstrong when he had his old power in the mid-1960s; Joe Muranyi had been with him in those slightly erratic 1967 and 1968 years and didn’t feel it was “that sad” but rather somewhat normal for the types of concerts he was capable of in his post-1970 comeback. He’d open with trumpet playing on “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” and “Indiana,” sing “What a Wonderful World,” play again on “Hello, Dolly” and that was about it; if he was feeling extra good, he also played on “Pretty Little Missy” and “Someday You’ll Be Sorry.” The rest of the set was devoted to All Stars features and numbers on which Armstrong only had to sing. It was enough to get a good review from John S. Wilson in the New York Times after opening night:

The precarious nature of Armstrong’s health was hinted at in a syndicated column by Earl Wilson that ran in newspapers around the country on March 8. “Louis Armstrong, 71 on July 4, blew his famous horn when he opened at the Waldorf Empire Room though it took so much of his strength that he went to bed between shows. His wife said he had been in bed much of the month resting so he could blow the trumpet while performing with his All-Stars. Wilson also added, “Recovered, after a slight relapse last week, Satchmo has scheduled appearances in Las Vegas and Honolulu–and always man, he’ll blow that horn. He got a standing ovation–but then, he always does.” There’s no mention in the news of this “slight relapse last week” but that could be the dire shape he was in when visiting Zucker’s office.

Either way, it does seem as the two week-engagement went on Armstrong grew weaker and weaker, eventually getting physically sick in the elevator before one show. No recordings (and as far as I know, no photos) have ever surfaced from the Waldorf engagement and perhaps that is a good thing.

Armstrong did seem to rally on the closing night, March 13. Photographer Eddie Adams was there and wrote beautifully about what would be Louis Armstrong’s last public performance in this article, published and clipped out after Armstrong passed away on July 6:

In case you cannot read the above scan, here is the full text:

**********************

THE LAST TRUMPET NOTE

Only ‘Pops’ Knew When It Was

By EDDIE ADAMS

Associated Press Photographer T

he world lost a friend yesterday. His name was Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong. His friends called him “Pops.” He in turn called “Pops.” I first met him a little over a year ago at a Manhattan recording studio. He’s such a giant of the music world that it was a bit surprising to discover that he was really short—a little under 5-foot-6. There was about him that warm quality and easy smile that made you relax in his presence. He wasn’t playing his horn when I first saw him, but was singing with that gravel voice, “We Shall Overcome.”

When the recording session was over I met his cheerful wife, Lucille, who travels with him. Pops’ birthday was coming up on July 4. He would be 70. This became an opportunity for me to make more pictures of a man I admired. Ira Mangel, Pops’ long-time friend and personal manager, accompanied me to his unpretentious home in Corona. He was a zany sight as we entered his room—he was wearing Bermuda shorts and a Mets baseball cap. He was especially proud of a large personal tape collection of his entire life, music and friends. The tapes filled up a wall in a room on the second floor of his house. As I was preparing to leave he shouted “Be sure to take a look at my bathroom before you go.” I did. The bathroom was wall to wall mirrors.

The next time we met it was in Las Vegas. In his small dressing room at the International, bouquets of flowers scattered throughout made the room even smaller. There were only three people with Pops. The door opened slightly and a voice shouted, “10 minutes before showtime.” Lucille with a warm embrace kissed her man on the cheek and left to take a seat in the overcrowded dining room. Ira left the room to take a position outside the dressing room door. Only Pops and I were left. He sat on a chair facing a mirror ringed with lights, wearing his tuxedo trousers, a white shirt and bib around his neck. He picked up his horn, played a couple of notes, gently laid the shiny instrument on his lap and stared at it as though he was either spellbound or reminiscing. He looked frightened. Again came the voice through the door, “Five minutes.” This was a big night for Pops. It would be his first public appearance playing his horn after a two-year absence because of illness.

Death had rubbed shoulders with Pops twice during that time. But this was his night, Sept. 6, 1970. Wearing a bright smile, holding his horn in one hand, Pops came bursting out of the dressing room door—stopped abruptly—stretched out both arms and chuckled devilishly; “My debut.” Pops went on to play to a standing ovation. Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong had returned. The doctors said he wouldn’t play again. He said he would. He did. Friends packed his dressing room after the performance. Pops was happy. Only two hours earlier he was tense, I think afraid to go on. Now he loosened up and talked to just about everything during his early years as a musician.

I didn’t see Pops again until he opened at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York March 1. I wanted to give him a photograph I made of him in Las Vegas before the show started. Ira asked me not to go to his room. “Pops isn’t feeling too good this evening, he’s kind of up tight,” Ira said. I gave the print to Lucille who said, “I have just the spot for this at home.” I found out later that Pops wouldn’t let her take the picture home until he finished his two weeks’ engagement. He kept it in his suite at the hotel. I waited offstage for Pops. He wasn’t the same Satchmo I had seen in September. Now he was frail, seemed to be wasting away. He moved slowly, haltingly. Six months had made a very old man of Pops. He weighed 125 pounds. He needed help to climb three steps to the stage. That night, Pops ended his performance with a song about his life, “The Little Boy from New Orleans.” I think he was trying to tell us something.

After a standing ovation, Pops, Ira and I started for his suite, but through the lobby of the hotel a crowd of well-wishers and autograph seekers surrounded Pops. He obliged. A New York columnist latched on to Ira. The crowd disappeared Pops disappeared. At the far end of the lobby the light was reflected from his horn. It made me look up. I saw Pops walking away alone. He seemed in a daze, swaying as he walked. I thought he was going to go to his room. His doctor answered the door.

“He had tears in his eyes as he walked off the stage during his last night at the Waldorf,” said Ira. “In all my years with him, I have never seen him cry before. He played his horn like he never played before and even told his audience stories about his trips to Africa,” he said. That last night at the Waldorf when Pops walked off the stage. No one but Pops knew. He would never play publicly again.

**********************

Four days later, Armstrong had a major heart attack, ended up back at Beth Israel Hospital until May 8, and eventually passed away on July 6. As of this writing, no audio has turned up from the Waldorf. On June 23, Armstrong invited the media over to his home in Queens and he played trumpet for cameras in his den. No audio or videos of that moment have turned up either. And Dan Morgenstern remembers a local NY news crew visiting Armstrong at home for his July 4 birthday and Armstrong was apparently filmed blowing a little trumpet on the edge of his bed. Alas, that has not turned up either.

Thus, the above audio of Louis on The Tonight Show represents the last sounds we have of the golden Armstrong horn, the instrument that changed history. But it doesn’t represent the last video we have of Armstrong. During the Waldorf engagement, a camera crew attended one performance. We wish we knew where the raw footage ended up but when Armstrong died in July, a Hearst Metrotone tribute was assembled, hosted by Dr. Billy Taylor, and at the 9:40 mark is a short clip of Louis delivering the final emotional chorus of “Boy From New Orleans” at the Waldorf:

We’d like to close by re-sharing the David Frost Show clip from earlier, as that, too, ended with “Boy From New Orleans.” I, personally, have used this to end many lectures and there’s usually never a dry eye in the house. Watch the full performance and definitely pay attention to the ending where Armstrong thanks the fans, most likely knowing that the end was near, but he was still determined to go out giving his public nothing less than 100%: