“Satchmo Under the Weather”: Louis and Lucille Armstrong’s May 16, 1969 Tape with Louis and Claudine Panassie

Last week, while continuing my ongoing series on the reel-to-reel tapes Louis Armstrong made between 1969 and 1971, I came across Reel 87, which had an interesting catalog description, written by Armstrong himself:

“At Home in Corona–Statchmo [sic]–under the weather–Lucille–Claudine–Louis Panassie (THE SON OF Hugues)–Experimenting (with) the new Stereo Tape Recorder Which Lucille had Installed for Satch in his Den while he was in the Hospital. What a thrilling surprise for Satch when he came home from the Beth Israel Hospital.”

Here’s the page:

Wow, where to begin with all of that? I decided to tell the full story of the tape, but instead of just throwing the full 2 1/2 hour conversation up, I wanted to dig deep with context and backstories and share clips and visuals along the way. Well, it was a good idea, but I guess I got carried away, making over 20 audio samples and pulling in photographs, collages, a YouTube video and other assets from a variety of places. When I was about to his the “Publish” button, I looked at my lopsided post and said, “I can’t publish this as is–this deserves its own post.” This is that post and all I can say is grab some popcorn because we are about to spend a lot of time with this tape.

First, we must backtrack a little bit to 1968, when Lucille Armstrong began a major renovation of their Corona, Queens home. Around the same time, in the fall of 1968, Louis ended up in Beth Israel for the first time with heart and kidney trouble. Meanwhile, Lucille actually lived at a nearby hotel on Ditmars Blvd. for a bit while construction finished. Louis was initially released in December and was in rough shape, physically and mentally, but he had one thing to look forward to: Lucille had had his den completely overhauled and had a brand new stereo system put in, with new Tandberg tape decks. As detailed way back in the first part of this series, Louis had stopped making reel-to-reel tapes in the 1960s so this was probably a way for Lucille to entice her husband to stay home and reignite his hobby of making tapes instead of going back on the road–as we’ve demonstrated, it worked!

However, not long after returning home, Armstrong relapsed and ended up back at Beth Israel in in February for two more months in intensive care, the closest he had ever come to dying. While there, Joe Glaser had a stroke and was admitted to the same facility. Louis was released on April 5, but Glaser died on June 6, 1969. Thus, the May 16, 1969 tape at the center of this post comes at an interesting time, recorded after Armstrong’s two stints in intensive care but before the death of Joe Glaser, who was still in a coma at Beth Israel Hospital.

On May 16, Louis and Lucille were visited by Hugues Panassie’s son Louis and his wife Claudine, in America to set up the filming for what would eventually become the documentary L’Adventure du Jazz. The Panassies wanted to scope out the location and see if Armstrong would be up to answer some questions about New Orleans and to sing a bit of “That’s My Desire” on camera. Hugues Panassie was one of Armstrong’s oldest friends, having first met in Paris in 1932 (yes, he named Louis Panassie after Louis Armstrong). In 1969, Hugues published a French-language biography on Armstrong that wouldn’t get an American translation until after Louis passed away. But Hugues made sure Louis got a copy of the French edition–here’s the cover and Hugues’s inscription:

We will share many excerpts of the conversation with the Panassies, but not the complete tape as there are sound issues–Louis mostly stays away from the microphone and there’s a persistent buzzing–but also, for much of it, Armstrong doesn’t talk and instead listens to a recording the BBC sent him of two All Stars concerts the band filmed in London from July 2, 1968, right before he got sick. Louis fell in love with this tape, and sent copies to all of his fellow All Stars, writing to drummer Danny Barcelona on January 20, 1969 to call it, ” The most relax thing we’ve ever done. One + two sides. A concert on each side. ‘S’too much, man….P.S. When you hear this tape, you’re get homesick for your band. ‘Us.’ I know I can hardly wait to get back on the mound and in the Grove [sic] again. (Tee Hee)”

Armstrong dubbed these BBC concerts–for those who were with me when I started this series, they appeared on multiple reels early on, including Reel 25 and 27–and wanted his fans to hear it, to the point where he labeled the tape box for it “FOR THE FANS” (though he got the date wrong and put 1967 instead of 1968):

Armstrong’s wish did come true as eventually Brunswick Records released highlights from it on the 1971 LP, Louis Armstrong’s Greatest Hits Recorded Live, the first–and only–album with a “Produced by Louis Armstrong” credit.

Now, let’s dive into the tape itself. At the time this was recorded, Louis hadn’t made much use of his new tape recorders so he decided to go back to his old methods and just record a good old-fashioned conversation with a microphone. Sadly, as he got the hang of his new setup, he stopped that process almost entirely and instead utilized direct input while making new tapes, putting an end to all the “fly-on-the-wall” moments that make the 1950s recordings so special.

Still, at least we have this precious document, even if it represents Louis in a quiet, diminished state. We’ll open with a clip from near the very beginning where Louis immediately mentions his new stereo, before quickly saying goodbye to “Bernice,” who is Bernice Dixon. On June 1, Armstrong wrote an “Open Letter to Fans” (reprinted in Louis Armstrong in His Own Words) in which he talked about his hospital stays and how Lucille was with him the entire time, adding, “Of course Ernest Debman our House man whom has been with us for many many years and Bernice Dixon Who Has Also been with us for many many years. They held the Castle (I called Our Hour) down while My Dear Lucille visited me. Even our two dogs, german snouzzers [sic], Love Bernice and Ernie.” Here’s the audio:

Claudine soon notices what appear to be books on the shelves behind Louis, but no, Lucille corrects her, those are tapes, mentioning how there’s a lot more in the basement. Lucille then gives an eloquent appraisal of her husband’s tape collection, though she mentions some of it–such as dirty jokes–is not publishable! (Louis, we think, would have disagreed….)

A few seconds later, Lucille demonstrates the bells and whistles of Louis’s new Tandberg tape decks and how he was in the process of taking his old tapes and converting them to stereo (that didn’t quite happen). Louis then sets up the aforementioned 1968 BBC concert, talking about it and eventually spinning it. Louis Panassie helpfully adjusts the sound so it comes out of both speakers–the Armstrongs were still getting used to it, even after Til Sivertsen, Tandberg’s national sale manager, was sent to their home to teach them how to use the new equipment, according to Jeff Joseph. Here’s that sequence, with a taste of “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South”:

After “Sleepy Time,” Louis (Armstrong) shows how he could continue recording even with the speakers off, turning them on and off during “Indiana” and asking Panassie, “Well, Louie, how do you like my new gadget?” as herard here:

Louis Panassie then took over for a while, talking about his plans for the film, the importance of New Orleans, wanting Louis to speak about his memories growing up there, etc. (“For the French, New Orleans is something important, see?” Panassie says at one point.) Louis gets going a few times, ready to talk about Storyville and the old days, but Lucille stops him and tells him it’s going to be for when Panassie returns to film him. “Well, when you’re ready, I’ll run it down for you,” Louis finally says. “I’ll never forget those moments.” Claudine asks which era was Louis’s favorite–New Orleans, Chicago, New York, etc.–and Louis says, “At the time, I enjoyed them all, they were good.” This leads to an interesting discussing on dancing, with the revelation by Lucille that Louis was an excellent ballroom dancer!

Eventually Panassie asks Armstrong about favorite songs, which leads Armstrong to talking about his vocal quartet in New Orleans and singing a snatch of their theme song, “Down on the Amazon” (which Louis always called by its first line, “My Brazilian Beauty”):

This excites Panassie, who talks for a few minutes about the importance of this film and what it will mean for his father, “a marvelous thing for his health.” Panassie then thanks Lucille for picking them up in her Cadillac earlier that day, leading to a humorous conversation about Louis, who hadn’t driven a car in 20 years after getting too many tickets (“Your husband has a jazzy foot,” a judge told Lucille in a story Jack Bradley loved to tell, too). Louis eventually talks about how it’s nice having a driver and even when it comes to the trumpet, he likes having someone carrying his case (he compares himself to Jascha Heifetz, who had someone carry his violin). This next clip ends with a telling story of Louis sending his Plymouth car to his sister Beatrice in New Orleans but every time her husband drove it, the police arrested him because they were sure he couldn’t own a nice car like that and had probably stolen it; Joe Glaser eventually sold the car and just sent Beatrice and her husband the money. (Another answer to the question of why did Louis never move back to New Orleans….) Here’s the audio:

This is followed with some talk about Beatrice, whom Panassie wanted to visit. Louis points out that she was still living in the same house she was when Hugues Panassie visited her during the 1949 Mardi Gras when Louis was King of the Zulus. Panassie asks about Louis’s boyhood home and Lucille simply says, “It’s gone.” “Oh yeah, it’s a police station,” Louis says with a chuckle. “They got a police station. They tried to save it but I don’t know anything about that.” Asked if he ever intends to return to New Orleans for Carnival, Lucille interrupts and says, “We never intend anything. Whatever comes up, comes up. Whatever shall be, shall be. We never plan anything.”

The topic turns to the New Orleans Jazz Festival, coming up on June 1, with Panassie mentioning Count Basie coming and asking to get in touch with Willis Conover. The Armstrongs know the man who can help: Jack Bradley. For the next several minutes, they go through their phone book and attempt to call Jack multiple times at multiple venues, without any luck. But because Jack is such a big part of this site, here’s an edited clip of this segment:

So far, so good, but this next segment broke my brain, dear reader. In my imagination, I thought this tape with Panassie was one of the first Louis made when he got home from the hospital in April 1969, just as he was starting to renumber his tape collection, not getting around to cataloging it until hanging “Reel 87” on it sometime in the spring of 1970. All that is true–except the Panassie tape wasn’t one of the first Louis made and he was actually about 30 reels in! The big reveal comes in the next clip, which I will also transcribe and illustrate with the relevant early catalog pages below:

Armstrong: “That’s the time Ed Murrow was interviewing me down in the Colombia [actually the “Vieux-Colombier” in Paris] where Claude Luter played, and he did some talking for it. I keep a note of all of that, see, so when I write my story, I can look at this book and a whole lot of things, see.

Panassie: Ah yes, for writing your book, yes, I understand.

Armstrong: Well, yeah, to bring back my memories. And it’s on tape anyway, see.

Stopping the transcription to point something out. When Louis says “I can look at this book,” he’s describing his tape catalog and is most likely looking at this page of Reel 29:

Reel 29 features a dub of Edward R. Murrow’s original See It Now broadcast from December 1955 that became the basis for Satchmo the Great. If you look at the bottom of the page, Armstrong writes “Paris Club Colombia — Claude Luthier, Clarinet.” If you listened to the clip, Louis called the Vieux-Colombier the “Colombia” and even pronounced Claude Luter’s last name “Luthier” so he was most like looking at this page. But his very next line at 32 seconds in, is what me realize Armstrong was further along in the process than I gave him credit for:

Armstrong: “Whatever, Reel 30, now who all’s on the reel. There’s Barrett Deems, Squire Gersh, Trummy Young, Arvell Shaw, Velma Middleton, Booker Pittman–that’s way down in South America. Yeah, see what I mean? So when I want it get to that part and say something about them, I got it right here on this tape.”

Sure enough, here’s the page for Reel 30–the All Stars in South America, with all the names he listed to Panassie:

So now we know that Armstrong burned through at least 30 tapes in the first part of 1969, before and after his second intensive care stay, though if you recall (and I don’t blame you if you don’t!), a lot of the early tapes in this series were tapes that Armstrong originally made in the 1950s and just put a new number on so the process might have been fairly quick for many of those. (But for proof that the code will never be fully cracked, Reel 27 has material on it from April 1970, 11 months after Armstrong showed off Reels 29 and 30 in 1969! Clearly he had his own process that must have involved renumbering and reordering certain tapes as time went on, but it sure is migraine-inducing sometimes trying to figure it all out.)

Anyway, after pointing out the contents of Reel 30, Armstrong points something out that unintelligible to me and I’m guessing involved a visual cue of some sort (“That’s why I have this ??? see? What’s on this thing over there? Things like that”) before saying, “So when I have time for that–right now, it takes a lot of energy. I don’t want to tire myself out, see.” A thump of a cabinet can be heard as Armstrong begins going through records, showing Panassie each one, as heard in this next clip:

Here’s a rough transcription:

Armstrong: Here. I’ve got all my records right here. From way back there. My whole life story in this big record [most likely pointing out Satchmo: A Musical Autobiography]. Remember that one? I used to take that on the road with me and play it with my little hi-fi machine. I got ’em all. I got a lot records I made here with Earl Hines. The Mills Brothers there–remember those? Let me show something in Spanish. Concierto de Jazz. It’s the same tunes. I don’t know if you’ve ever saw it. So you know, I have a lot of fun. And here’s Jelly Roll Morton, all his life story about New Orleans. Someday I’ll put them on tape. There’s a lot of them. These are extra, other people’s records, I think. No, Satch Plays Fats. All the tunes Fats wrote. Gee, you come here, boy, and have a helluva time listening to that stuff.

Pannassie: Which record do you prefer?

Armstrong: Well, I’ve got to like ’em all. I’ve got to play them again to find out. As long as it sounds good, that’s all right. All my work in there.

Panassie: Yes, I see. A novelist’s work.

Armstrong: I’ve got some Italian songs and all this stuff I made there, see. From way back.

There’s a lot to unpack in that passage because Louis did indeed get to everything he mentioned. Concierto de Jazz was a Spanish edition of his Decca LP Jazz Concert, already dubbed by Louis on Reel 1 of this series, though it made appearances on multiple tapes thereafter. Jelly Roll Morton’s Library of Congress recordings appeared on a few early tapes before getting a more thorough taping on Reels 49-52. Reel 53 included a dub of Satchmo: A Musical Autobiography, though that set, too, popped up multiple times, as did Satch Plays Fats and the 1968 Italian sides. Reel 68 included 1928 sides with Earl Hines, the 1968 Italian session, and an LP compilation of his Decca recordings with the Mills Brothers, all mentioned above. It’s pretty interesting to me that Armstrong probably had his records lined up up in no particular order, but when making these tapes, he grabbed them right off the shelf and dubbed many of them in the order he stored them.

(P. S. for children of the 1960s–does any of that background music sound familiar? After NBC’s “In living color” announcement, a show begins with a voiceover about “Swinging London.” The voiceover becomes hard to hear but a musical cue plays loudly and more songs are heard as the tape goes on. My hunch was it’s an episode of the Kraft Music Hall, which aired from London on May 14, but if Panassie and Lucille are correct later on when they say it’s May 16, here’s NBC’s rundown for that evening, after a daytime filled with game shows, soap operas, an airing of the film Six Black Horses and the evening news: High Chaparral at 7:30, Name of the Game at 8:30, The Saint at 10–hmm, Roger Moore’s Saint was in color by 1969 and took place in England so maybe it’s that?)

After Panassie asks Louis to wear the same pink shirt he was wearing at the time when he comes back to film him, Armstrong then gets back to his tape catalog, mentioning that Louis’s father Hugues is in his index. He continues in this next clip:

Transcription:

Armstrong: “There’s a whole lot stuff that I recorded from the radio and searching for it, the things that I want. See now, there’ll be a day coming when I just put what I do personally up further and put all this behind. It takes a lot of time. I can’t do it now, I’ve got to rest right now. See, I’m getting ready to go back to work–there’s Fats Waller. You’ve heard of him, you know, Fats?”

Again, interesting insight that probably explains the run of tapes that feature only Armstrong’s own music, as he was attempting to “put what I do personally up further and put all this [other people’s music and broadcasts] behind.” Armstrong was clearly still thumbing through his records and was struck by one by his dear, departed friend, Fats Waller. This seemed to open up a melancholy streak in Armstrong, who asked Panassie if he ever met Jack Teagarden or Velma Middleton, discussing their passing. After detailing Velma’s untimely demise, Armstrong talks about his present health woes and even brings up Joe Glaser, at the time in a coma at Beth Israel, eventually passing on June 6:

Transcription:

Armstrong: “But I just figure when your time comes, you know. I had two setbacks and I’m still here to tell about it. I enjoyed my time, that’s all and I appreciate that. Now all I got to do is scan my life back and see what I was doing wrong, man. Like I didn’t get enough rest. I was always afraid I was going to miss something, you know. That’s the way we hurt ourselves. I came up with the fellows that were on their way out anyhow. I had good doctors. Same as Mr. Glaser, that’s the doctors I had, his doctors. The only thing, he didn’t drink or smoke either but he was up all hours of the night watching acts and booking acts and in that office, screaming at everybody. So that put him down. So that’s the thing I have to cut out. I don’t have to work as hard as I used to. What good is it? You come out just the same.”

Such a statement from Armstrong would have been unfathomable just a few years earlier as he famously hated days off and vacations and preferred to blow his horn day in and day out. Now after staring at death’s door twice, he could admit that he perhaps he worked himself too hard and vowed to never do that again.

Panassie, perhaps sensing some weariness in Armstrong’s barely audible voice, changed the subject, asking about the musicians in band, improvisation, and other broad subjects before a very quiet Armstrong talked about going back to work, naming “Blueberry Hill,” “Mack the Knife,” “Hello, Dolly!,” and “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” as songs he’d do if he went back to performing. Even though he had just admitted that he worked too hard, he was now ruminating about when he could go back. “When I go back to work,” he says, “that’s why I warm up a little every day with trumpet because all I have to do is strengthen my lips now and I can go back to work like I never laid off. Because the band, they all know what I’m going to play.”

Panassie then goes on for awhile about his ideas for the film, with Armstrong going along before eventually talking about how “comfortable and cozy” his home is. Because the theme of this site is still technically “That’s My Home,” here’s a short clip of Armstrong talking about his home and how he wanted the Panassies to feel relaxed:

Transcription:

Armstrong: Well, now that you see my home and how it’s set up and how comfortable and cozy, you can come in with any idea you have, and we don’t have to think so business-fied. You know, it’s just wonderful if we can just sit around here. That’s what I wanted you to feel, that’s why I wanted you to come out here. I wanted to you to see this.

Panassie: I hope you can glad of the final results.

Armstrong: Oh yeah, always glad to have you. And you won’t have a lot of people around disturbing you. We have our usual company and things like that, but it’s no open house and all that stuff. That’s why I’m recuperating so quick.

Panassie: I think so, yes. You are very friendly for me.

Armstrong: I want you to feel relaxed.

Panassie: You feel me relaxed, yes.

Armstrong: That’s how I want you to feel.

This next audio excerpt is a longer one, too long to transcribe, but it’s fairly interesting. Louis talks about the tape they’re making and says that Panassie could “rub it out”–meaning erase the tape–if he wants, but he thinks it’ll be “good to have in your files when you go back to Paris.” Armstrong then mentions that he might copy the tape and keep a copy for himself–we’re glad he did! “We’ll have one apiece,” Armstrong says, “for the files–for posterity or something and I think you’ll enjoy that.” This isn’t the first or last time Armstrong used the phrase “for posterity” on this tapes, something that clearly meant that these were here to stay. After the talk about the tape, the rest of the clip finds Armstrong giving his daily routine, including when he woke up, went to bed, had supper, played trumpet, and his exercise: walking the length of the first floor of his home ten times, twice a day. Here’s the audio:

Panassie then asks the status of the All Stars. Lucille says, “Some of them are working in between. Because, you must remember, it’s been since September. And a lot of those fellas to sit around. A lot of them are working. Buddy Catlett is working with some band. We must realize that Louie, when he goes back to work and he wants his band, if they’re not available, we’ll have to get someone else.” Louis responds, “Now, if it wasn’t going to be such a long wait, or something, they would have been on half salary.” Lucille: “Well, they were on half salary for a short while, but we couldn’t pay them half salary all this time. Not just this time.” Pops: “Six months is too long.”

Panassie then asked exactly why Armstrong ended up in intensive care, leading to this explanation by Louis and Lucille:

The clip begins with Panassie asking if Louis had a disease. Louis and Lucille immediately get defensive and Lucille says, “When he first went in, it was for the kidney. The kidney affected the heart so the second time was the heart. The kidney affects all the whole body cause this is the pump really. This is the waste, it purifies everything in your body. If the kidney fails, everything fails.”

A humorous story about Louis’s visit with a proctologist follows, which gets pretty graphic but results in some big laughs. “So the doctor, he said, ‘Two more inches I have to go.’ I said, ‘Ohhhh, Lord have mercy!’ So he went the two more inches and he tells me when he finished, he said, ‘Thank God you have no disease, and no cancer or anything.” So don’t let anybody tell you I had a disease because between that and Swiss Kriss and that piece of iron down there, that told everything. That kept all the diseases. So this kidney trouble and the heart come from other things like overwork, no rest, probably had one nip too much, you know.”

But asked about how thin he was looking, Lucille responds that yes, Louis is 136 pounds now but was weighing 120 pounds before he went to the hospital. “The doctor didn’t want him to be that small, but Louis wanted to get small like when he was 10 years old,” Lucille says. “When I was 20 years old,” Louis corrects her, before insisting, “I wanted that! But the doctors said, ‘No, put on more.” But Louis admits, “Now I’m satisfied” and reminisces about how bad the second stay in the hospital was. “54 years, I didn’t know what a rest looked like,” he says. “I told all my musicians, was low, you know, pushing it. I won’t do that again. Have less and live longer. I’m very much satisfied with the outcome of everything, although it kept me out.”

Panassie eventually mentions that no one knew Armstrong was in the hospital at first and even Joe Glaser downplayed it when questioned by Hugues. According to Louis and Lucille, that was by design, as explained here:

According to Panassie, Glaser wrote Hugues to say, “Why are you so afraid? There’s nothing too important. Please stay quiet.” “The public’s so funny,” Louis says, before Lucille adds, “They would not let the publicity get out cause immediately, as soon as you say you’re sick, the first thing they say is you’re dying or you’ve got something. In fact, he was in the hospital for over a month before the public knew it. Glaser wouldn’t let [it be known publicly].” It’s true; a search of Newspapers.com shows that Louis was admitted in February 1969, but no newspaper reported it until March 12.

After such a heavy discussion about Louis’s health, Panassie mentions that he heard a photographer was there recently to shoot the bathroom. Yes, Lucille responds, for House Beautiful magazine (we actually don’t have this in our Archives so if anyone out there has the March 1969 issue with a spread on bathrooms, let us know if the Armstrong’s mirrored one is featured!). When Panassie assumes photographers and reporters must regularly visit, Lucille says no, and speaks a bit about the importance of privacy:

At this point, Armstrong remembers that at least one of his tape boxes has a photo of Hugues Panassie on it and becomes determined to find it. He puts the 1968 BBC concerts back on and starts shuffling through tapes, many of which we’ve already seen as part of this series. For this “show and tell” section of the tape, we’ll share a bunch of short video clips followed by the visuals of what they’re looking at.

First, the famous Swiss Kriss “keyhole” photo. At first Lucille is reluctant to show Claudine, saying, “She’s too young,” but they eventually pass it around and have a big laugh at it. Louis mentions he’s sent it to Hugues and gives Jack Bradley credit for designing it. Here’s the audio:

And here’s that photo on what became Reel 67:

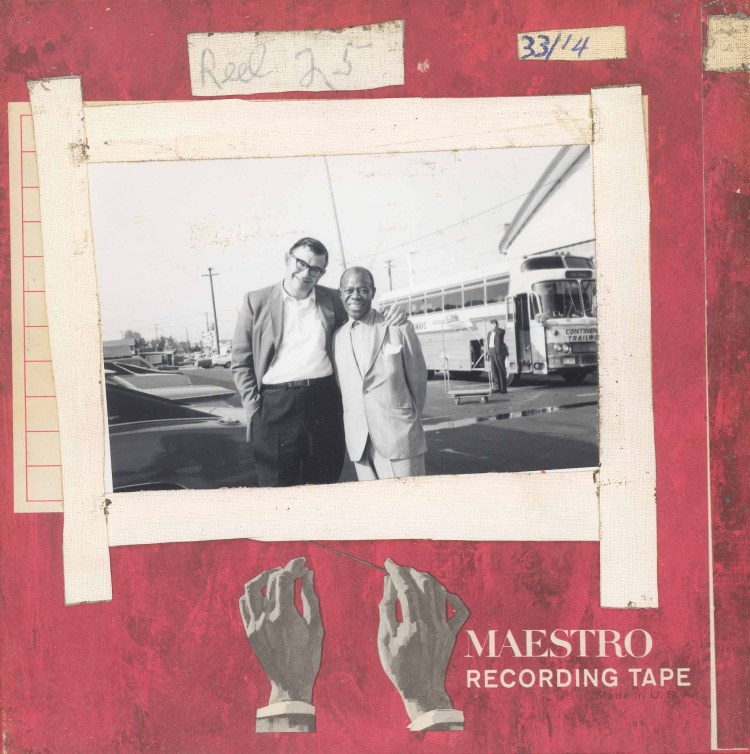

Next, Louis sees a tape box with a photo of the marquee of the Chicago Theater in 1955, when Louis and the All Stars shared the bill with Gary Crosby. Louis reads the names, reminisces about Crosby dancing with Velma Middleton, and even identifies the man in the photo as “Run For Cover”–great nickname, but we wish we knew his real name! Louis then flips over the box and shows a photo of himself with All Stars clarinetist Joe Muranyi. Here’s the audio:

And here’s what they’re looking at, the front and back of Reel 25:

In the next clip, Lucille, also sounding confused about Louis’s methods, asks how many of these boxes are empty. That’s actually a small clue into Louis’s methods as it appears a lot of these collages were done earlier and then once he finished making a tape, he’d put the tape in the box, put a number on it and then catalog it, so it’s possible many of the collage boxes were empty at this point. Louis then points out a photo of Lucille in Blackbirds of 1936 that appears on one of the boxes:

Again, we recently saw that photo on Reel 69, covered in white tape, which was probably added, along with the reel number later, but the box with the photo was already extent in May 1969:

Louis then pulls out Reel 24 and mentions the “German girl” on the front–Gabrielle Clonisch–and he and Lucille struggle to remember the bassist on the back (who honestly is a mystery; I identified him as Billy Cronk when I first wrote about this tape but am no longer so sure). Here’s the audio:

Here’s what they’re looking at:

Claudine Panassie then asked if Lucille helps Louis with the collages and she replies, “Oh, this is his room. Everything in here, I set it up, but it belongs to him and he does what he wants with it.” Louis says, “This is where I keep all my pictures, you know.” After identifying a girl on one of the tape boxes who used to dance with them in Boston, Louis Panassie compliments him, saying, “Everything is very well done, very clean.” Lucille responds, “Well, that’s Louie,” to which Louis states, “That’s my hobby.” In keeping with the “That’s My Home” theme, here’s that clip:

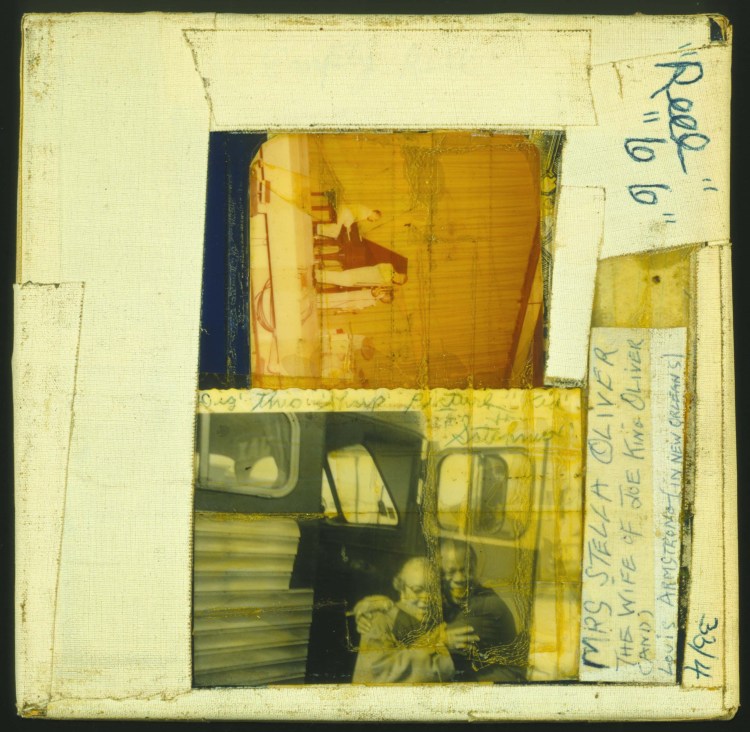

Next, Louis and Lucille find a tape box Louis originally made in the 1950s featuring a photo of himself, Billie Holiday and Leonard Feather from 1947. This is a good example of a collage that Louis did not redo during this 1969-1971 run so we still have it today with the original number–Reel 423–and it’s really not in the best shape with the original Scotch tape no longer affixed. Louis seemed to be aware of the problem even back then as Panassie must point out the fragile condition, leading Armstrong to say, “That’s all right. Once I fix them again, that’ll last another ten years.” So even he knew that reinforcing them with the new white tape was something of a method of preservation. In between, there’s another discussion of Louis’s weight, brought about by a tape box spotted by Claudine, which I have a guess about that I’ll provide below. This somewhat longer clip concludes with Louis showing off a box that featured a photo of King Oliver’s widow, Stella–here’s the audio:

In order, here are the collages discussed in that clip, opening up with the brittle one with Armstrong, Billie Holiday, and Leonard Feather:

This is speculation, but clearly a photo catches Claudine’s attention regarding Louis’s weight–perhaps it’s the image on the other side of that box, taken when Louis was on the heavy side in 1953?

And just for the heck of it since weight has proved to be a theme of this post, here’s a reel that features a photo of Louis at his heaviest, another contender for the one discussed in the above clip:

And finally, the Stella Oliver collage, which we recently covered as Louis retaped it and renumbered it as Reel 66:

As Louis continues pulling tapes with one rare photo after another, Lucille finally asks, “Where do you keep finding all these pictures of me? I haven’t seen them in years.” “Well, they been up there,” Louis says, “I just ain’t been around to them, you know. I just ain’t been around to them. I get a kick out of looking at them so that’s what I do for the experience of finding the one I want you know.” Louis then repeats that he was trying to find one with Hugues Panassie before saying, “See the work you can give yourself right here at home, huh? So don’t say I don’t have nothing to do. I have plenty to do if I just want to, you know? But right now I think I’ll just concentrate and blow a little and I just got a new album, they sent, just published, you know, so I’ll go along with that.” Here’s the audio of the above:

Finally, the end of the evening arrives, with Louis and Lucille offering to pay for a cab to pick the Panassies up and take them to their hotel, which they’re very grateful for. Here’s an edited clip of the segment, where you can also hear Lucille on the phone ordering the cab and giving the address 34-56 107th Street, now the Louis Armstrong House Museum of course:

While waiting for the cab, Lucille takes Louis Panassie into another part of the house to test out something involving electricity, leaving Louis with Claudine, who notices a bottle of French cologne. Louis excitedly talks about it (“I don’t want nobody to be smelling like me,” Louis says. “I keep my own version of smell”) and even goes to his bathroom to show her a French soap he got from Hugues Panassie and Madeleine Gautier. Finally, a horn blows and the cab comes to take the Panassies away, concluding a memorable night in Corona:

That part of the tape ends there and I’m assuming the Panassies didn’t take this tape home with them; I do wonder if Louis made a copy of it for him. But I personally love the ending, as Louis sweetly thanks them and asks them to call him when he gets to the hotel. What a beautiful host!

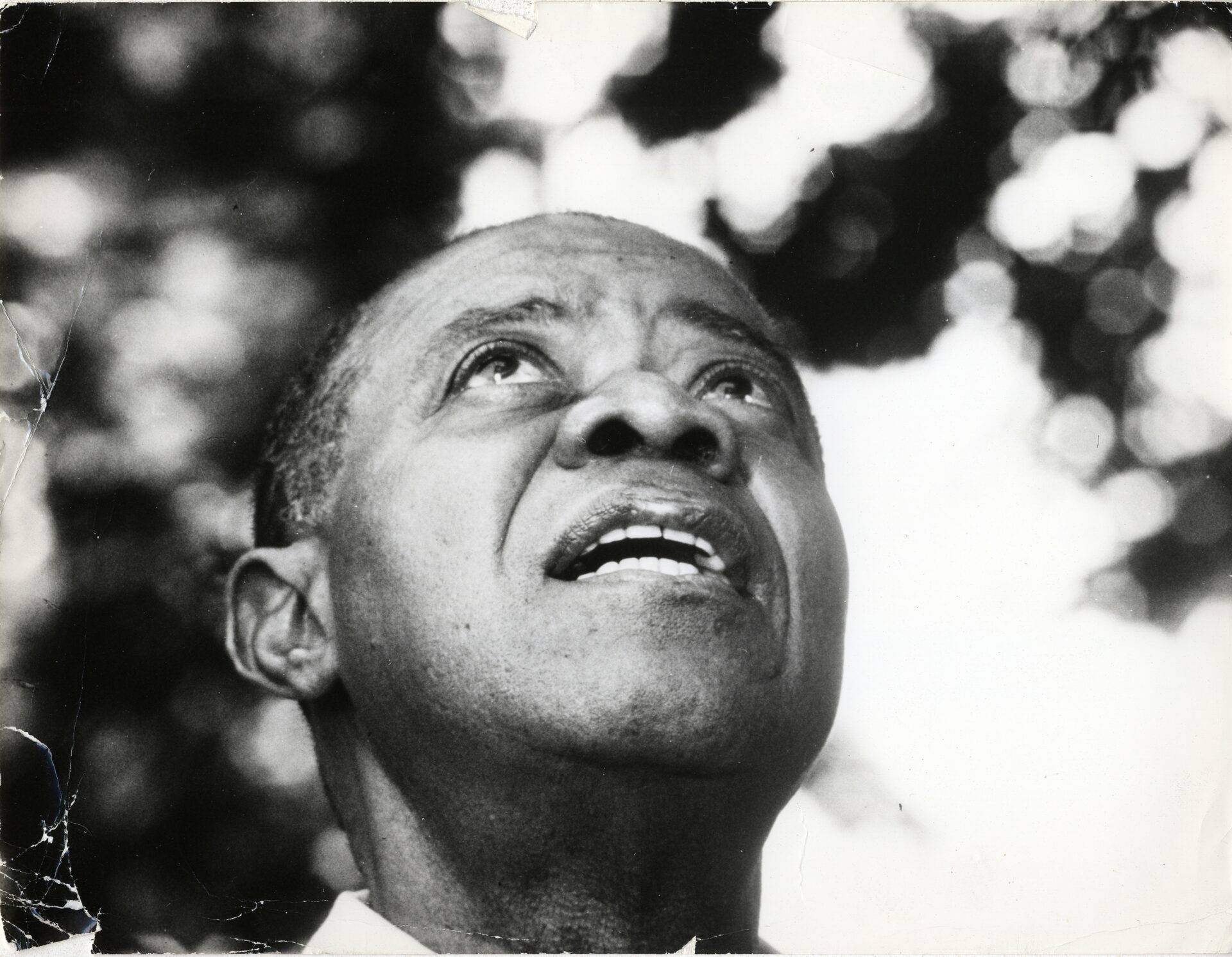

One month later, on June 17, 1969, Louis and Claudine returned to Corona to film Louis in his backyard. The bad news is the finished film L’Adventure du Jazz has never been available in the home video or streaming era, but the good news is Louis Panassie himself uploaded immortal footage to YouTube of Claudine teaching Armstrong to sing “That’s My Desire” in French! Here’s the clip (and Louis wore the pink shirt Panassie requested):

And here’s one more 5-minute compilation Louis Panassie posted from L’Adventure du Jazz with a few more clips of Louis in it (as well as a host of other jazz legends):

Priceless footage, isn’t it? Louis Panassie also sent three photos to Lucille Armstrong’s close friend Phoebe Jacobs, one of his father in his office under a portrait of Louis, but also two striking photos from the 1969 backyard session:

With that, Louis and Claudine Panassie went back to France, working on L’adventure du Jazz until it was completed in 1972. As a postscript, here is Louis Panassie’s condolence letter, sent to Lucille after the passing of Louis in July 1971:

Here’s a transcription:

July 16th, 1971

dear Lucille,

Please accept our deepest condolences. Claudine and I, among thousands of people all over the world, are yet a little more able than others to understand how deep is your sorrow and heavy your burden: you were two to give us the warmth of your hospitality in Corona. I shall call when I go to N.Y. this summer, and go and pay you my respects, and also pray on your husband’s grave.

Sincerely yours,

Louis Panasssie

“You were two to give us the warmth of your hospitality in Corona.” I can’t think of a better way to end possibly the longest entry in “That’s My Home” history. Thanks for reading and if you liked it, leave a comment and perhaps we will do similar deep dives on some of the other priceless tapes in Louis Armstrong’s collection in future posts.