“The Greatest Photo Taker”: Remembering Jack Bradley Party 57–Life After Louis

Jack Bradley, Louis’s Armstrong’s close friend, personal photographer, and greatest collector, passed away four years ago today, on March 21, 2021, at the age of 87. In the days after his passing, I began writing what I thought would be a single tribute post to my late friend–but it soon became the start of a 56-part series. Earlier this year, we thought we might have hit the end of the road when we published a post about Louis Armstrong’s funeral and the establishment of the New York Jazz Museum the year after. But now, on the four-year anniversary of Jack’s passing, we thought we’d continue the saga with a look at Jack’s life, post-Louis.

We’ll pick up the story in 1973, also the year of many major tributes to Louis in the New York area, all of which were attended by Bradley. On June 25, the Rainbow Room hosted a lavish New Orleans Jazz and Food Festival with Lucille Armstrong as the guest of honor. Bradley served as disc jockey, spinning nine hours of Armstrong records, but he also managed to take a few photos, including this one of Lucille with David Frost and Dr. Billy Taylor:

Bing Crosby also dropped by and Bradley managed to get a photo of him sitting with Lucille:

Three days later, Bradley appeared on John Wingate’s WOR radio show alongside Lucille, Ella Fitzgerald, and Stanley Dance. He didn’t take a photos, but we do have the audio of that entire broadcast and will share it at a future date. Two days later, on June 30, Bradley was a guest on an Armstrong tribute on Joe Franklin’s WOR radio show with Lucille, Illinois Jacquet, Russell Jacquet, Sy Oliver, Dan Morgenstern, and Phoebe Jacobs. We don’t have the audio of this one but Bradley did manage to take a photo of the other guests present:

Then, just four days later on July 4, 1973, the Singer Bowl was renamed Louis Armstrong Stadium, a story we told in detail in this post. We don’t have the negatives from this day, but we do have prints of two of Jack’s photos, including this one of Lucille on stage, with George Wein standing next to her:

Bradley also managed to take another photo of Louis’s sister, Beatrice “Mama Lucy” Collins, who traveled up from New Orleans alongside Louis’s half-brother (Willie Armstrong’s son) Henry Armstrong:

The other big event that took place in the summer of 1973 was the unveiling of Louis’s headstone in Flushing Cemetery, two years after he passed away. This time, Lucille personally invited Jack to the ceremony; here’s her invitation:

Bradley attended and took many photos; we’ll start with an image of Louis’s footstone:

The tombstone before the unveiling:

That’s Pastor John Gensel looking on as Lucille unties the ribbon:

The unveiling; that’s Louis’s adopted son Clarence Hatfield Armstrong on the far right:

Pastor Gensel speaks:

A moment of prayer; I must admit, except for Al Cobette on the far left, Lucille, and Clarence, I’m unable to identify many of the faces in this photo. If anyone has any ideas, please leave a comment:

Afterwards, Jack took a few photos of Lucille with the headstone:

That’s Phoebe Jacobs in the background; anyone know who the man is?

A note about the trumpet on top of the headstone. According to a press release at the time, “Dominick Fasolino, who made the monument, said that he rejected making the trumpet of granite or marble and chose bronze imbedded into the stone itself, as a more effective deterrent to vandalism. One of Armstrong’s trumpets with a cloth handkerchief draped from it, was photographed from many angles, to serve as the model for the trumpet on the tombstone.” Lucille saved one of the snapshots of the trumpet that was used as a model:

The efforts to thwart vandalism were ultimately successful but not after too many challenges. After numerous failed attempts to pry the bronze trumpet from the top of the tombstone, it was removed and replaced with white plaster trumpet, which is how it appears today. The original bronze trumpet top resides in our Archives today; here’s a closeup of it at the dedication:

Jack also took a photo of Louis’s longtime friend “Creole” Pete Robertson at the headstone (not sure who the woman is):

Bradley also took a close-up photo of a floral tribute sent by Grace Kelly, then the Princess of Monaco:

After the dedication, Bradley was invited back to Lucille’s home for reception with food. This color snapshot was found in Lucille’s collection and shows some of the gathering chowing down in the Armstrong’s backyard garden. There’s Lucille front and center, Dr. Gary Zucker on the right of the middle row, Pastor John Gensel on the back right, Stanley Dance (I believe) on the top right, and Jack Bradley in the top center, wearing a red coat:

Next to Jack is his girlfriend at the time, Nancy Eckel. Nancy later recalled that it was at this occasion that Lucille told her, “You know that Louie and I always felt that Jack was our son.” Here’s audio of Jack talking about his relationship with Louis and Nancy telling the story about Lucille to Michael Cogswell and David Ostwald in 2008:

It was also in the summer of 1973 that Bradley shared an exciting announcement: the New York Jazz Museum, where he served as Managing Director, received a $140,000 grant from the Ford Foundation “to continue the expansion of its archives and publications, presentation of living musicians, a touring program for schools, colleges and universities and other activities devoted to maintaining jazz as a living form as well as a historical and cultural asset.” Bradley curated exhibits for the Jazz Museum, including one of his Louis Armstrong memorabilia:

The following year, a chunk of Jack’s Armstrong collection received a great deal of visibility when it was featured on the cover of the Atlantic LP, Satchmo Remembered. The album was a recording of a tribute to Armstrong held at Carnegie Hall on November 15, 1974 with music by the New York Jazz Repertory Company. Instead of featuring a photo of Armstrong on the cover of the LP, Atlantic featured an assemblage of Bradley’s Armstrong artifacts, as designed by Joan Hall (who donated her copy of the LP to the Armstrong Museum last summer!):

Unfortunately, by the time Satchmo Remembered was released in 1975, the New York Jazz Museum was enveloped in turmoil brought about by the tension between Bradley and the Museum’s Executive Director, Howard Fischer. By October 1975, Lucille Armstrong, George Avakian, Red Balaban, Stanley Dance, John Hammond, and Artie Shaw resigned from the Board and Bradley resigned his role as Managing Director. What happened next is a bit murky but Bradley apparently had to leave much of his memorabilia–including Willie “The Lion” Smith’s piano–at the Museum. He did manage to salvage his photographs, negatives, and Armstrong memorabilia, but the whole incident sickened him so much, he made the decision to leave New York City for good.

He headed to Cape Cod–specifically Harwich, Massachusetts–where he married longtime girlfriend Nancy Eckel on August 22, 1976. Here’s a photo of the newlyweds, courtesy of our pal Michael Persico–notice they’re each wearing matching “Louis Armstrong 1900-1971” t-shirts!

This was the start of Jack’s new life. While Nancy earned a steady paycheck teaching high school Spanish, Jack took advantage of the the busy tourist season on the Cape–not to mention his proximity to the ocean and his Coast Guard training–and began operating a charter boat, the aptly named “Jubilee.” Here’s one of Jack’s fliers:

Shortly before his collection ended up at the Louis Armstrong House Museum, Jack and Nancy put together a collage that included the above flier, Jack’s high school diploma, his Coast Guard certificates, and multiple photos from the 1980s and 90s, including Nancy wearing Jack’s old “Louis Is God” shirt and a photo of Jack meeting then-First Lady Hilary Clinton at the Louis Armstrong House Museum in 1999:

That took care of the warm weather months for about the next 40 years–but what about the rest of the year? Bradley might have left the Jazz Museum, but he surely didn’t leave jazz.

In September 1979, Lucille Armstrong came up to Brandeis University in Boston for a tribute to Louis. Bradley was asked to curate an exhibit of some of the highlights from his private collection–here are some photos, beginning with the Satchmo Remembered tableau (in case you’re curious, we still have the original board, but the various components are spread across the Jack Bradley Collection in our Archives):

And in black-and-white:

Lucille received co-curator credit:

A selection of photos, along with an award, a statue, and an Armstrong trumpet:

A case of records, letters, magazines, and more:

A young fan, modeling one of the t-shirts Bradley was selling:

Bradley also formed the Cape Cod Jazz Society, which held its first jazz festival on Memorial Day weekend in 1980–here’s the program cover:

Naturally, the last page of the program featured a photo Jack took of Louis Armstrong on the set of Dial M for Music in 1970:

In 1987, the Cape Cod Jazz Society devoted an entire issue of its Jazz Notes periodical to Bradley, offering his life story and many tributes from his friends. It’s definitely worth sharing in full:

Jack was quite content on Cape Cod but occasionally was lured back to the New York area. He served on the committee of the Armstrong Memorial Committee at P. S. 143 in Corona, Queens, which was renamed the Louis Armstrong Elementary School in 1977. On May 18, 1984–six months after Lucille Armstrong passed away–Jack was invited to the a ceremony at the school in which artist Elton C. Fax donated an oil portrait of Armstrong. Naturally, he brought his camera and took some photos of the school, which must have been a thrill to see:

Bradley also took some photos of the unveiling of Fax’s portrait:

Armstrong’s friend Al Cobette was present with one of Louis’s trumpets:

Phoebe Jacobs addressed the students:

The following year, Phoebe Jacobs became Vice President of the Louis Armstrong House Museum and helped make the deal for Queens College to administer the Louis Armstrong House and Archives. In 1991, Queens College hired Michael Cogswell as Archivist and in May 1994, the Louis Armstrong Archives opened to the public. Bradley did not attend any of the initial events, but Cogswell was soon made Director of the Louis Armstrong House and invited Bradley to serve on its Advisory Board. Cogswell invited Bradley to visit the Armstrong House in January 1995 and fortunately, brought along his camera, as well as two special guests, George Avakian and David Ostwald.

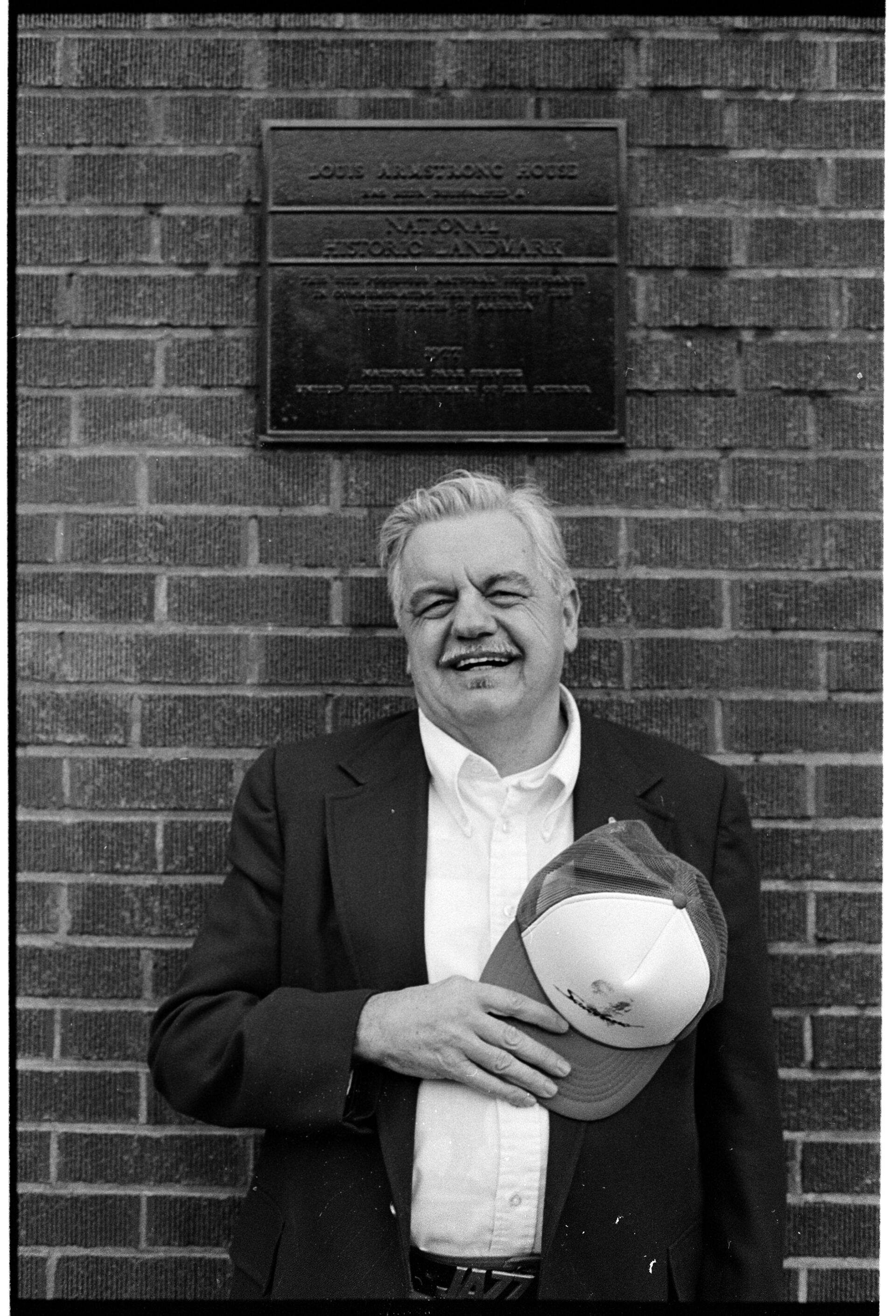

Here’s Bradley in front of the National Historic Landmark plaque in front of the Armstrong House:

Avakian in front of the plaque:

Ostwald, Avakian, and Cogswell in front of the “New York City Music Trail” sign outside the House:

In this next photo, you can see the abandoned property across the street that is now the home of the Louis Armstrong Center!

Bradley had to take a turn under the sign, too:

Once inside the House, Bradley couldn’t resist taking a few photos:

Bradley photographing the downstairs, mirrored bathroom:

From there, it was over to Flushing Cemetery, where Lucille was now interred:

22 years after the dedication, Bradley was photographed with Armstrong’s tombstone:

Then it was over to the Queens Museum, where the Smithsonian traveling exhibition, “Louis Armstrong: A Cultural Legacy,” curated by Mark Miller, was in its final days after four months:

Here, Cogswell was joined by Assistant Director Jorge Arevalo, Phoebe Jacobs, and George Wein:

Bradley took this photo of Wein in front of a striking painting of Louis, painted by Oliver Johnson, while he was in Attica Prison in 1977 (this painting was donated to the Louis Armstrong House Museum after Wein’s passing in 2021):

A photo of Bradley and Wein together:

While in New York in 1995, Bradley was also invited to an epic hang at David Ostwald’s Upper West Side apartment with Cogswell and Avakian; here are a few photos from the occasion:

1995 was also the year the United States Post Office created a Louis Armstrong stamp. Bradley had lobbied for this for several years and received some credit for his efforts in this article by John Basile:

Here’s an alternate take of that beautiful photo of Jack, taken by Barry Donahue:

In April 1996, the Louis Armstrong Archives mounted its first exhibit of Bradley’s Armstrong collection, titled, “Louis Armstrong: I’ve Got a Heart Full of Rhythm.” Bradley made the trip to Queens and posed for a joyous photography with David Ostwald, Phil Schaap, Marty Napoleon, George Avakian, and Walter Schaap:

Bradley continued to regularly visit Queens College in the late 1990s, sometimes giving presentations, sometimes serving in his role on the Advisory Board of the Armstrong House, as depicted in this photo with Jimmy Heath, Michael Cogswell, Phoebe Jacobs, and David Ostwald, among others:

Here’s Cogswell and Bradley in the Reading Room, perhaps in the middle of a presentation:

In 1998, High Times magazine inducted Armstrong into its “Counterculture Hall of Fame,” awarding him with a “Cannabis Cup.” Cogswell sent Bradley over to Amsterdam to receive it on Armstrong’s behalf. After having the time of his life at the ceremony (her served as a judge in a marijuana competition), Bradley brought the treasure back to the Archives, where it was added to the collection. Here he is posing with it alongside Gwen Schaeffer and Milton Mezzrow, son of Louis’s friend (and marijuana contact), Mezz Mezzrow:

By 2001, Bradley turned his sights to New Orleans, attending the dedication of Louis Armstrong International Airport and the first annual Satchmo Summerfest that year. Bradley brought his camera and got some black-and-white photos with Nancy inside and outside of Armstrong Park:

In our institutional collection, we have a few photos of Bradley in action at Satchmo Summerfest, photos possibly taken by Michael Cogswell. Bradley was a fixture from 2001-2006, showing Armstrong footage–using the actual 16mm films and projector!

Here’s Bradley after a panel with Dan Morgenstern and Joe Muranyi:

And Bradley simply having a marvelous time taking in the music of Armstrong’s hometown:

In October 2003, the Louis Armstrong House Museum finally opened to the pubic. The very first Gift Shop sale? A box of Swiss Kriss, sold to Jack Bradley! (That’s pianist Chuck Folds in the background and then-Assistant Director Deslyn Dyer making the sale.)

By this time, Cogswell had set in motion the plan to acquire the Jack Bradley Collection for the Museum’s growing Archives. Cogswell and then-Archivist Peggy Alexander spent countless hours in Bradley’s home, photographing everything and making inventories. Here are a few photos from these early-2000s trips:

Jack and Nancy in front of Jack’s “Vinyl Resting Place”:

Just a tiny glimpse into the boxes and boxes stashed all throughout the house of Bradley’s Armstrong photos and memorabilia:

Cogswell and Alexander typed everything up, Dan Morgenstern visited Jack and appraised the collection, and a proposal was submitted to the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation–who agreed to purchase Bradley’s collection for $480,000, paying for it in six installments of $80,000 per year, donating everything (including the rights to Bradley’s Armstrong photos) to the Louis Armstrong House Museum. Bradley had one request: he could not bear to see everything go at once. Because he was getting paid in six installments, he would agree to Cogswell and his team coming up once a year to take materials back to Queens. He would need some time to decompress between each visit.

In 2005, Cogswell and Kendall Albert made the first trip, packing up a cargo van with over 2,000 of Bradley’s Armstrong’s records, plus hundreds of books and periodicals. Here’s a photo of Jack, Nancy, and Kendall with the first van, ready to go to Queens:

Now, I normally do not write about myself on this site and I’m not about to start now; after Jack’s passing, I wrote a tribute, “In Loving Memory of Jack Bradley,” on my personal blog which really tells the rest of the Bradley saga through my eyes. For those who don’t know, I was hired by the Louis Armstrong House Museum in October 2009 as part of an IMLS grant specifically given to arrange, preserve, and catalog the Jack Bradley Collection. My second day on the job was a trip to Cape Cod for what we believed would be the final haul of the Bradley Collection; I even got my own van photo like the one above:

It turns out, we didn’t quite get everything and to make another trip in 2010. This time we brought along ailing All Stars clarinetist Joe Muranyi for an emotional reunion. They greeted each other by simply saying, “Survivors.” I was also able to share the work I had been doing in cataloging and digitizing Jack’s photos; I cherish this photo, taken by Michael Cogswell:

Joe Muranyi passed away in 2012 and Jack’s health soon started to deteriorate, as well. He hadn’t been back to the Armstrong House since 2005 and it appeared that he might never make it back to New York. In 2014, though, I co-curated an exhibit, “Treasures from the Jack Bradley” collection that received a lot of buzz, including an article in the New York Times. Jack was curious and thanks to truly heroic efforts by his close friend, Mick Carlon–including shoveling snow outside of Jack’s home–he had one last hurrah of a trip in February 2015. Here’s Jack, Mick, myself, and Ben Flood in the Armstrong House Kitchen:

Bradley was overcome with emotion when he hit the Den, the room where he spent so much time with Louis, and sat behind Armstrong’s desk to take it all in.

The next day, it was over to Queens College, where Bradley was reunited with Michael Cogswell:

And I was able to show him the new and improved state of his collection, all boxed up, catalogued, and safe in our Archives:

We even made it to Birdland that evening for a performance by David Ostwald’s Louis Armstrong Eternity Band (celebrating their 25th anniversary there this May!). It was great to see Jack reunite not only with David but with Dan Morgenstern, 50 years after “The Slivovice Interview”:

Jack never made it back to New York after those two crazy days in 2015, but he was kept quite busy up on the Cape, where he had started working with Mike Persico on trying to make sense of the rest of his collection. You see, the deal with the Armstrong House was only for Jack’s Armstrong collection, but his house was still overflowing with photographs and artifacts pertaining to the other major figures in his life, like Duke Ellington, Bobby Hackett, Earl Hines, Ruby Braff, and more. Mike soon began discovering more Armstrong images in the crevices of Bradley’s home and would deliver them to Queens when passing through New York.

But in 2017, Mike alerted us that Jack’s health had taken a turn for the worse. Quickly, Michael Cogswell, David Ostwald, and I headed up to the Cape, expecting to say our last goodbyes–but we were immediately greeted by Jack…standing up and rolling a joint! He rallied for our visit and we had an absolute ball. I gave him a hard drive with scans of all of his Armstrong photos and negatives and took some time to show him some newly discovered Armstrong footage. Here we are, doing just that, with Mick Carlon looking on:

One last selfie with Jack and Nancy:

Somehow, Jack hung on for four more years, even outliving Michael Cogswell, who sadly passed away in April 2020. Though I never saw him again, we talked on the phone once or twice a year, always a memorable time. I do want to share one more photo from that 2017 visit as it is of the crew that really kept him going those final four years, Nancy, Mike Persico, and Mick Carlon:

Mike came up with the idea of doing something more with Jack’s photos. Originally conceived as a documentary, the idea grew into a live performance with a band of New England’s finest traditional jazz musicians playing songs associated with Armstrong, all with Persico telling tales of Jack in between each song, while Bradley’s photos would be shown on a slideshow. Jack was energized by the prospect and put in a lot of time, helping identify photos but at his already advanced age, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s and slowed down even further. The pandemic soon hit, scuttling the live concert idea. Jack was eventually moved into a nursing home, where he passed away four years ago today.

But there’s a happy ending! After the pandemic subsided, Persico got his live concert idea off the ground, eventually setting up a 501c3, Classic Jazz Visions. Under this banner, Persico has performed his live tribute at various venues in the Northeast, including the Louis Armstrong House Museum. Persico also finally oversaw the production of a book of Jack’s jazz photos; titled Classic Jazz Visions: The Photographs of Jack Bradley, it can be purchased online or by visiting the Louis Armstrong House Museum.

Thus, four years after he took his last breath, the saga of Jack Bradley is alive and well through the thousands of photographs he captured from the late 1950s onward. His photos were used throughout the 2022 documentary Louis Armstrong’s Black and Blues, and it was particularly nice to see an image of Jack and Louis in that film’s trailer. I thought I knew everything there was to know about Jack and Louis and the Jack Bradley Collection, having worked on it for 15 1/2 years, but I learned something new with each new post in this series. Thank you to those who have been with me from the beginning and who are still here–57 posts later.

I’d live to give Jack the final word. During that 2008 conversation with Michael Cogswell and David Ostwald, Bradley ruminated about the changes he witnessed in the perceptions of Armstrong over the years. In the 1960s, it was not “cool” to like Louis Armstrong and many jazz musicians teased Bradley for how much he loved Pops and was always going to see him and hang out with him. And by 2008, Bradley felt vindicated, that the history books had proven him right–here’s the audio:

That’s Jack Bradley, folks. I wish he was still here in 2025 so he could see the Louis Armstrong Center. I’m sure he’d be tickled to see his photos hanging in a state-of-the-art Museum dedicated to his hero–and friend.

Thank you, Jack Bradley. We miss you.

(As laginappe, a video the staff of the Louis Armstrong House Museum made in tribute to Jack in 2022.)