“We Want Louis!”: 65 Years of “An Evening For Hungary” at Royal Festival Hall

65 years ago today, on December 18, 1956, Louis Armstrong performed for one-night-only at Royal Festival Hall in London. Writing about it afterwards in the Melody Maker, Max Jones called it a “triumph” and added, “Armstrong felt it as a kind of climax to his career.” Yet, with very few photos, no video, and no commercially available audio, this “climax to his career” has mostly flown under the radar when it comes to tackling the many triumphs of Armstrong’s storied career. But a quick survey of our Archives show enough newspaper clippings, photos, and yes, AUDIO, to make it ripe for the “That’s My Home” Virtual Exhibit treatment.

(A note as we approach our 100th “That’s My Home” post. We started this site at the height of the pandemic to highlight our Digital Collections with a theme of “Hey, we’re all stuck at home–what did Louis Armstrong do when he was at home?” But we are now starting to move away from the physical location of Armstrong’s den to tell more stories from the many places he traveled, starting today in London. Thanks for the continued support and we look forward to keeping these Virtual Exhibits going for years to come!)

The story actually begins in Soviet-occupied Hungary on October 23, 1956, when a student demonstration in Budapest turned into a full-on anti-communist revolution. However, on November 4, Soviet tanks entered Budapest and effectively crushed the revolution, driving residents to flee the territory. By mid-November, 180,000 Hungarian refugees had fled to Austria and 20,000 had fled to Yugoslavia. “Within a few days of the first refugees arriving, a massive effort was launched to resettle the Hungarians,” according to a 2006 United National High Commissioner for Refugees article. “Over the following months, they were transferred by bus, train, boat and plane to 37 different nations on five continents,” according to the UNHCR. “The United States and Canada each took in around 40,000, while the United Kingdom accepted 20,000 and Germany and Australia some 15,000 each. Two African and 12 Latin American countries also took in Hungarians.”

These countries soon went into overdrive to organize fundraisers for the refugees. In London, a Hungarian Relief Fund was set up by Lord Mayor Sir Cullum Welch, who had the idea to put on a special fundraising concert, featuring Louis Armstrong as the headliner, fronting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. Armstrong had already made a wildly successful tour of the United Kingdom in May 1956–shortly after the British musicians union lifted its long-standing ban on American musicians from performing in the country–and now they wanted him back.

There was only one problem: the concert was to be held on December 18, when Armstrong and his All Stars were to be in the middle of a Christmas week engagement in Miami. But Armstrong and manager Joe Glaser realized that the Hungarian Relief effort was an important one and rescheduled the $22,000 Miami appearance for February so Armstrong could perform in London, even paying his own traveling expenses out of pocket (but not the All Stars, who stayed home for some rare time off, as the concert was originally envisioned as featuring just Armstrong and the Royal Philharmonic).

As Armstrong told Britain’s Picture Post magazine, “When the Lord Mayor of London asked me to play at the Festival Hall for the Hungarians you be sure I’m gonna do it just as sure as there’s white on rice.” Armstrong also gave credit to the man who was really responsible for the behind-the-scenes aspect of his visit, the Honourable Gerald Lascelles, first cousin of Queen Elizabeth II and quite a jazz fan in his own right. “Gerald Lascelles sent me my timetable for this gig,” Armstrong told the Picture Post. “Gerald is a great youngster. There’s an old New Orleans chief in Paris and whenever I come to town he fixes me up a mess of dishes that just makes me think of home. I took Gerald and his wife along. When it came to that red beans and rice we all just tore out together. So in my satchel I’ve got a recipe for Red Beans and Rice for Mrs. Lascelles.”

The news of Armstrong’s performance hit the wires on November 23 in a United Press International story. According to a later mention in the Chicago Tribune, tickets sold out for the concert within a day. “The staid Royal Philharmonic Orchestra has let its hair down and invited jazz king Louis ‘Satchmo’ Armstrong to join in a concert to benefit Hungarian refugees,” the Associated Press wrote on December 1. “The American trumpeter accepted the invitation extended and will appear Dec. 18 with a full symphony orchestra. Princess Margaret will be guest of honor.”

By this point, fundraising efforts for the Hungarian refugees were in full effect in the United States. “This central Pennsylvania community is pouring itself–materially and spiritually–into an all-out effort to aid refugees of the Hungarian revolt,” a December 3 AP story read. “The effort began spontaneously several weeks ago when refugees of Communist oppression in Hungary began to pour into Austria and the United States moved to take many of them into this country. The American Friends Service Committee issued an appeal for aid–clothes, money, whatever people could spare. But in State College, a community of some 17,000, the appeal suddenly took root, became personal and compelling. Donations began to flood in. Results: Literally tons of clothing have been collected around the town’s Christmas tree.”

Coincidentally, Louis Armstrong performed at Pennsylvania State University that same week. The AP reported, “World famous jazz trumpeter Louis (Satchmo) Armstrong, at the university for a concert, got interested, donated his coat to the local drive and announced he expected to make a concert tour of Europe with proceeds to go to Hungarian relief.”

One of Armstrong’s offstage hobbies was saving clippings of news stories that featured him, eventually taping them into a scrapbook. Here’s a scrapbook page filled with Jet blurbs from November and December 1956, including an announcement of the Hungarian Relief concert on the bottom left, second from the bottom:

On December 7, the Black Press of America published more details of what the concert would feature: “Gerald Lascelles, chairman of a committee set up to arrange the visit, said Armstrong and the conductor, Norman Del Mar, were giving their services free. It is hoped that the concert of both classical and light music will raise more than $158,000. The program will include music by Kodaly, the Hungarian composer; Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, and Variations on a Jazz Theme which Armstrong is writing specially for this concert.”

Though that last item sounds exciting, a follow-up UP story on one of the Royal Philharmonic’s rehearsals cleared up the confusion: “The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra brushed up today on its hot licks and blue notes in preparation for next week’s appearance of guest artist Louis Armstrong. The Royal Philharmonic more accustomed to the crashing drums of a Beethoven symphony or the lilting violins of a Strauss waltz, rehearsed a complicated new score with the imposing title: ‘Variations On Jazz Themes Associated with Louis Satchmo Armstrong.’ The program will include such Dixieland classics as St. Louis Bleus and Mahogany Hall Stomp, and the Chicago-style West End Blues.”

Meanwhile, back home in the States, Armstrong was working right up to the last minute before his flight. On December 11, he kicked off the monumental Satchmo: A Musical Autobiography sessions, waxing six selections that day and six more on December 12 (including the immortal “When You’re Smiling”). On December 14, Armstrong performed in front of 3,000 fans at the Mosque in Newark, NJ. Backstage, he was questioned about the new music on the scene, rock ‘n’ roll. “It’s music, too,” Armstrong told the Newark Star-Ledger. “Anythin’s music if they know how to do it, but it’s nothin’ new, it’s out o’them ole churches. No, boy, that ain’t for me.”

Finally, on December 16, Louis and Lucille Armstrong made their way to London, barely making the flight according to Armstrong’s “diary” in the Picture Post, reprinted here:

If you can’t read it, here is Louis’s pre-show diary:

Picture Post December 31, 1956

Blowin’ for Hungary

By Louis Armstrong who gives Picture Post his own diary of the London visit

SUNDAY afternoon, Idlewide [sic] Airport, New York. Can’t hardly get my breath. We had a mad dash from our house in Corona, Long Island, and just got to this plane as they were fixing to roll away those stairs. Been playing one-niters for 40 long years, and never had a closer call. And now I’m gonna settle down and try to scribble y’all a few lines.

[…]

Monday morning, 8 am., London Airport: I heard all about this gas rationing in London, but everybody seemed to get out here somehow. Thought I was going to be cold in London. But that [trumpeter] Mick Mulligan just opened up and warmed the place up beautifully–leaving everybody in the best of spirits. And, early as it was, I just had to limber up my chops on his horn too. Our driver, Mike Owen, who took us all around the country last May, was there and bustled us into his big car to take us to the Dorchester Hotel where we’re staying this time.

Usually when I play a concert I have my All Stars but they’re back home getting a little extra Christmas vacation. So Humphrey Lyttelton has rehearsed a little group called my British All Stars to help me out. And you can believe me, this little band can wail. Oh yes, they can blow awhile. Jack Parnell, Dill Jones, Lenny Bush just playing all over that bass, Sid Phillips, and a cat who can really gliss, our team man, George Chisholm. Boy, did they jump! Oh! Oh! Look at the time. Got to get over to the television station. And then home to the hotel to get into my tux for the musicians banquet. Be seein’ y’all.

Same Day, midnight The musicians Banquet. Twenty-five years ago, when I first came to London, the musicians gave me a banquet, and here they are doing it once again. Imagine how good that makes ol’ Satch feel. Humphrey Lyttelton is in the chair. Bandleaders and trumpet players everywhere you look. Oh, we scarfed a fine meal that Jack Isow served us. And we all sipped and nipped. And you know there was some music. But that’s the kind of music you only hear when musicians get together and play for just kicks. It comes straight from the heart. I could stay all night.

Tuesday evening, Royal Festival Hall. When I came backstage tonight I had to manoeuvre my way through (looked like) a million fans and reporters with their cameraman flickering-and-flashing so fast until it looked just like daylight. When I got up to my dressing room there was John Huston who flew over just to dig this concert. And there was ‘Doctuh Pugh, setting out my handkerchiefs and mutes and stuff. Noel Coward had sent me his special dresser whose name is Smasher Hatton. I’ve been warming up all day, you know just a few minutes every hour. And my chops are in great shape for this great occasion, a high water mark of my career. What an audience. It glitters just like a wedding cake. Well, that’s my cue. S’long folks.

God bless you and keep you. Always. Am Red Beans and Ricely yours Louis Satchmo Armstrong.

The Picture Post also included this wonderful Haywood Magee photo of Louis taking a rest in his London hotel room, still grasping his trumpet:

Getty also owns an alternate Magee photo of Armstrong warming up in his hotel room:

The above “diary” represents Armstrong’s side of the story, but naturally, the press was waiting to cover his ever move. Eddy Gilmore was an Associated Press writer who befriended Armstrong during his May trip, turning in a long profile that became famous for its tales of Louis directly addressing Princess Margaret at Empress Hall (dedicating “Mahogany Hall Stomp” to her!) and his response to a question about folk music (“Why, Daddy, I don’t know no other kind of music but folk music—I ain’t never heard a [horse] sing a song.”)

Gilmore was back at it in December and wrote another Associated Press story on Armstrong’s return. We actually don’t have a physical copy of this article but thanks to Newspapers.com, we know the text appeared in dozens of newspapers on December 17; here’s a transcription:

SATCHMO

Cousin of Queen Greets Trumpeter at London

By EDDY GILMORE

LONDON (AP)—Louis Armstrong blew into London today to play his famous trumpet for Hungarian relief.

The 56-year-old Jazzman who learned his music in a New Orleans school for waifs found himself in select company.

At the airport to welcome him was the Hon. Gerald Lascelles first cousin of Queen Elizabeth II, and the Marquis and Marchioness of Donegal.

“Satchmo” said the Hon. Gerald, “all London welcomes you.”

“Thank you Daddy,” said Armstrong. “It was a rough flight over the ocean from New York but I’d fly anywhere in the world for Sir Cullum Welch, the lord mayor.” Armstrong will appear at Royal Festival Hall tomorrow night accompanied by the 100-piece Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, for the Lord Mayor of London’s Hungarian relief fund.

Sir Laurence Oliver will introduce the trumpeter and the lord mayor will speak.

Despite the first day of gasoline rationing a small jazz band and 50 Armstrong fans showed up at the airport to greet Satchmo.

“What’s that button in your lapel?” a British reporter asked.

“That’s my fraternity button,” said Satchmo. “Some college fraternity made me a member.”

“College?” asked the puzzled reporter. “I didn’t know you ever attended college.” Satchmo, who never went beyond the fifth grade, replied, “Well sir I’ve played at an awful lot of universities.”

“What did you take up at College?” persisted the reporter.

”Everything that wasn’t nailed down,” laughed Armstrong.

**********

Meanwhile, Armstrong was again asked for his thoughts on rock ‘n’ roll, this time from a United Press reporter. Armstrong’s response gave the UP a short story that was also placed in dozens of newspapers on December 18:

[Note that that’s technically a misquote as Armstrong’s standard line about rock, which he used until his dying day, was “old soup warmed over.”]

With the press out of the way, it was time to start rehearsing for the big show. As mentioned above, Armstrong’s All Stars weren’t flown over but he wanted a similar combination to wail with so trumpeter Humphrey Lyttelton put together an all-British small group with George Chisolm on trombone, Sid Phillips on clarinet, Dill Jones on piano, Lennie Bush on bass, and Jack Parnell on drums. Here’s a Melody Maker photo of the group in action:

Armstrong was very pleased with the “British All Stars” but things hit a snag when he began rehearsing with the Royal Philharmonic and its somewhat impatient conductor, Normal Del Mar. Once again, the United Press was there to cover the tension in a wire story (The New York World Telegram and Sun ran it with the headline “Satchmo Doesn’t Dig the Maestro On Those British Bom-Bom Beats”):

“Louis (Satchmo) Armstrong and his Royal Philharmonic Orchestra tried to shake it down again today to make their ‘bom-boms’ come out even.

‘I don’t dig you,’ the trumpeter told impeccable conductor Norman Del Mar, a protégé of Sir Thomas Beecham. They were running through ‘Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.’

‘Something ain’t right,’ Satchmo insisted. ‘At the end of this bar I’m supposed to go home—like this.’ He blew a G loud and clear. ‘Right?’

‘Well, these other cats,’ he said, pointing his trumpet at the Royal Philharmonic ensemble, ‘why, they’re going bom-bom. They’re a bom behind, or I’m a bom ahead.’

Director Del Mar studied his score. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said earnestly. ‘That’s the way it’s written here. There’s no time to re-orchestrate it.’

‘Re-orchestrate nothin’,’ said Armstrong with a smile. ‘Let’s roll it that way—grab it boys, we’re off.

And they went—through that, ‘The Lonesome Road’ and ‘Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego.’

‘You finished before we did, Louis,’ Del Mar complained.

‘Don’t matter at all, at all,’ Louis said and smiled. “

**********

It wasn’t a good sign of what was to come, though Del Mar did show a sense of humor by agreeing to take a photo with Louis, with the conductor attempting to blow Satch’s trumpet:

Of that first rehearsal, drummer Jack Parnell remembered, “Playing with Louis was a magnificent experience and during rehearsal he said to me: ‘After my solo, you take a drum break.’ I had seen some of the score and had to say to him: ‘Pops! We can’t. The orchestra comes in here,’ and he rasped: ‘They can’t go on until we stop.’” Battle lines were drawn….

Finally, it was the night of the concert. Here is a photocopy of part of the program from our Gösta Hägglöf Collection:

Jack Bradley wasn’t on the scene yet but his collection contains a couple of paragraphs by Lascelles, including a description of “St. Louis Blues,” that also must have come from the original program:

Writing about the concert in 2002, Jim Godbolt noted, “The British Musicians Union, surprisingly, in view of their political associations with Communist Russia, had given permission, but forbade any recordings being made, although giving BBC TV sanction to film. In the event, no television cameras were present….”

Now, dear readers, if you’ve made it this far, here is our gift from the holidays. It turns out the concert was recorded, though about in as far from a professional manner as possible. Trumpeter Humphrey Lyttelton had a feeling this was going to be an important night and wanting a souvenir, placed a reel-to-reel tape recorder in a backstage dressing room, capturing the sounds onstage as piped through a monitor. It was a pretty primitive way of recording the proceedings but without Lyttelton’s ingenuity, we wouldn’t have an aural document to share of the concert–so beggars really cannot be choosers in this instance!

A copy of the tape found its way into our Gösta Hägglöf Collection, which is what we will be sharing in this post. It’s a somewhat crude document as not only is the sound quality subpar, but there some jarring edits with sudden starts and stops (and only 28 mostly inaudible seconds of Sir Laurence Olivier’s intermission speech). And once again, we have watermarked it with regular beeps to prevent any unauthorized use (though I doubt anyone would issue something that sounds like this commercially).

With the caveats out of the way, sit back and enjoy one hour of prime 1956 Louis Armstrong, playing marvelously with his British All Stars and teaming up with the Royal Philharmonic–until the whole event turned into “shambles,” as will be detailed below. But first, the audio!

It’s something else, huh? A few observations are in order before we get to the press coverage. Lyttelton didn’t record the Royal Philharmonic’s performances of the “Tragic Overture” or “The Firebird Suite,” instead switching it on during the start of Armstrong’s first feature, the “concerto grosso” arrangement (by Alfredo Antonini) of “St. Louis Blues” that Armstrong famously played while Leonard Bernstein conducted for the film and album, Satchmo the Great, in July 1956. Armstrong is in spectacular form but throws his first curveball of the evening with his seemingly impromptu call of an encore. This is something he also did with Bernstein at Lewisohn Stadium and took him a second to catch on there, too! Here, everyone joins in until the very end when poor drummer Parnell forgets to take a break, leaving an awkward silence. Armstrong simply counts out the allotted four bars and takes it into the stratosphere himself for a satisfying ending!

Next comes the mystery of the tape: on Hägglöf s copy, Armstrong’s standard opener “Indiana” follows, a feature for him and the British All Stars. This seems to make sense and is corroborated by Perry Cater in the London Daily Mail, who wrote, “Satchmo and the orchestra did the ‘St. Louis Blues’ stylishly. Then Satchmo and the jazz corps d’elite in mid-platform surged into ‘Indiana,’ a famous New Orleans number….” But the UP article noted that after “Sleepy Time Down South,” Armstrong “started singing an unscheduled chorus of ‘Back Home in Indiana’ and then groaned the lyrics of ‘Mack the Knife.’” Multiple press reported listed “Mack” as an encore which would seemingly put “Indiana” towards the end, something Hägglöf himself agreed with when he rearranged his taped copy onto a private, homemade CD. But given the UP reporter’s misjudging of Armstrong “singing” “Indiana,” I tend to go with the London Daily Mail and the actual order of the tape and feel that Armstrong sprung “Indiana” on the unsuspecting musicians and audience immediately after “St. Louis Blues.”

That closed the first half of the concert, with Olivier making his intermission announcement, of which only the aforementioned 28 seconds survive on the tape (the press notices below quote him a bit more). Oddly, no photos seem to have survived of the actual concert, but Getty has one backstage shot of Armstrong and Olivier together:

Del Mar and the Royal Philharmonic opened the second half with Hungarian composer Zoltán Kodály’s “Háry János Suite,” which also went unrecorded. Armstrong then returned for what I feel to be one of his all-time greatest versions of his theme song, “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South,” which uses Gordon Jenkins’s 1951 arrangement as a point of departure but has more spots for Armstrong’s horn, including a glorious concluding cadenza.

A medley of spirituals followed, opening with “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.” Some laughter can be heard early on, which we can only speculate about. Bassist Lennie Bush told a funny story about this performance that isn’t borne out by the recording, but it’s worth sharing (perhaps it happened at the rehearsal?). “Del Mar was a very pompous fellow, totally out of sympathy with Louis and referring to us as ‘those jazz people,’” Bush told Ronnie Scott’s Newsletter in 2002. “One recollection is Louis singing a medley of songs associated with him, including Nobody Knows The Trouble I’ve Seen, which, to the audience’s delight, seeing him struggling with the 80-piece RPO, changed the title to ‘Nobody Knows The Trouble I’m In – JESUS!’”

“Nobody Knows” segued into a spectacular version of “Lonesome Road,” a piece Armstrong burlesqued on his only other two surviving renditions from 1931 and 1955. This version is an instrumental and is quite passionate, Armstrong taking the melody up an octave at one point, prodded by powerful drumming by Parnell. A real magical moment.

The medley of spirituals concludes with Armstrong’s 1938 Decca hit, “Shadrack,” always a fun one. In concert, Armstrong usually paired it with “When the Saints Go Marching In” so it made sense to kick off the “Variations on Jazz Themes” portion of the program with “The Saints,” the orchestra doing its best to keep up with Armstrong’s regular All Stars routine–including another impromptu encore, this time sans the Royal Philharmonic.

Next, another highlight in a concert full of them, a special version of “West End Blues.” Other versions survive from this era, notably on Ambassador Satch and The Great Chicago Concert, but Armstrong somehow sounds even stronger here than those earlier attempts. (Pet peeve: when discussing Satchmo: A Musical Autobiography, some pundits are quick to point out the absence of “West End Blues” as some indication that Armstrong no longer could adequately play it. Well, here he is, knocking it out of the park the same week he began the Autobiography sessions! It wasn’t included on that 4-LP set because Columbia had just released their Ambassador Satch version, not because he was daunted by it.) Also, listen for Armstrong’s obvious delight in pianist Dill Jones’s solo, exclaiming to the audience, “He plays so smooth there!”

With applause still ringing out from “West End,” the Royal Philharmonic unfurls a long introduction that culminates in a ponderous, bordering on pompous, reading of the opening phrase of Spencer Williams’s “Mahogany Hall Stomp.” A tasty drum break by Parnell takes care of the Philharmonic’s portion of the arrangement, leaving Armstrong and the Brits to their own devices to swing “Mahogany Hall” for the next five minutes, Armstrong in superb control over the landmark three-chorus solo he originally minted in 1929, and calling for yet another exciting encore.

The planned finale for Armstrong and the Philharmonic was “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue,” the orchestra setting up Armstrong’s opening cadenza–and immediately stepping on his toes. It sounds like an accident on first listen–but then read the articles below and tell me what you think! After Armstrong and the small group play the melody and Phillips takes a clarinet solo, it appears the rest is going to go down in typical All Stars fashion….but no! Armstrong hits a high note, holds it and modulates in the key of Ab, just as he did on his famed 1938 Decca recording. Unlike the Decca, Armstrong only takes one chorus in the higher key instead of two, but he sounds great and still has enough chops for a big ending, with support by the orchestra.

And with that, Armstrong was supposed to take his final bow and head offstage to let the Philharmonic close the proceedings with Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody”……except the crowd wouldn’t let Armstrong leave the stage. Armstrong wasn’t one to ignore his audience’s wishes so he quickly called a small group performance of his big recent hit, “Mack the Knife.” Perhaps sensing that if he ended it cleanly, he’d be through for the night, he signaled for Parnell to take a drum break at a faster tempo and came back in with “Royal Garden Blues,” really turning on the heat during his solo and the concluding ensemble choruses.

Press reports say that at some point during the encores, a defeated Del Mar took a seat and put his head in his hands. Armstrong finally left the stage but the crowd wouldn’t stop chanting “We Want Louis!” It’s at the end of the audio file above but it’s so exciting, here it is again, separated from the rest of the concert:

While all of that was going on, Del Mar stood in place and waited for it quiet down so he could begin the “Hungarian Rhapsody”…..but with no end to the chanting in sight, Del Mar threw in the towel and exited the stage. Armstrong was ready to go back out and play some more, but impresario S. A. Gorlinsky physically took the trumpet out of Armstrong’s hands and refused to let him go on.

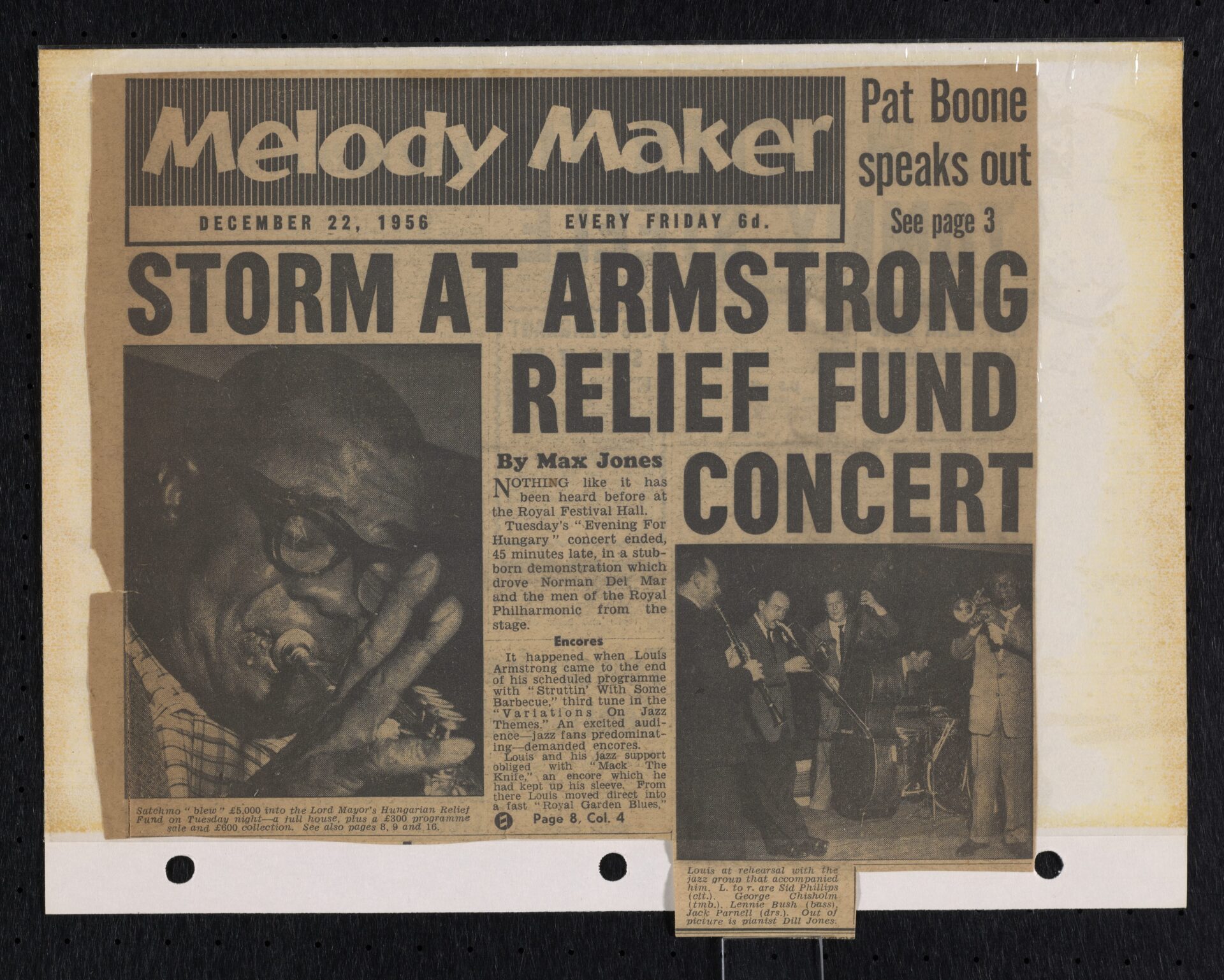

The wild, bitter ending to “An Evening For Hungary” immediately overshadowed all that preceded it. The next day, the press had an absolute field day with it, especially when Del Mar told them that the concert had become a “shambles.” Here is the powerful Melody Maker story by Max Jones (with some more rare photos from before and after the concert):

We realize that’s a bit hard to read with the small font and a chunk of one column missing but we were able to piece it together with a complete photocopy elsewhere in our Archives to present the following transcription:

NOTHING like it has been heard before at the Royal Festival Hall. Tuesday’s “Evening For Hungary” concert ended, 45 minutes late, in a stubborn demonstration which drove Norman Del Mar and the men of the Royal Philharmonic from the stage.

Encores

It happened when Louis Armstrong came to the end of his scheduled programme with “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue,” third tune in the “Variations On Jazz Themes.” An excited audience—jazz fans predominating—demanded encores. Louis and his jazz support obliged with “Mack The Knife,” an encore which he had kept up his sleeve. From there Louis moved direct into a fast Royal Garden Blues,” quite obviously unrehearsed but none the less amusing for that.

When it was finished Louis’s part was over. The programme stated that the concluding item would be the RPO’s interpretation of Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody” No. 2. Then the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Cullum Welch, was to speak.

In the event, neither of these performances took place. The majority of the people there had accidentally come to hear Armstrong. They had heard a lot of him, but not enough.

They clapped and stamped and shouted. Minute after minute the uproar continued. At first conductor Del Mar smiled tolerantly. The smile gave way to a pained expression.

It was no wonder. He was not, so far as I know, to blame for the planning of the programme. And I doubt whether he had previously formed an accurate opinion of Armstrong’s attraction for a British crowd.

I felt a little sorry for Mr. Del Mar. Unfamiliar as he must have been with the ways of jazz audiences, he waited long and silently for a chance to beat in the ‘Rhapsody’—described to me as the ‘Flying Home’ of the classical orchestras.

But if he and his 80 or so players remained silent, they were about the only ones to do so. A surprisingly large number of apparently ordinary people seemed agreed that if the couldn’t have Armstrong they would not on any account have Liszt.

In the face of the storm, there was little that even the dignified Del Mar could do. Armstrong suggested afterwards that “the professor should have played ‘The Queen,’ at least.” That, said Louis, “would have sealed it right up nice.”

But the two relevant anthems had been performed at the start; and then, of course, there were, officially, the “Rhapsody” and the Lord Mayor to come.

After some five minutes of uproar, Del Mar indicated that the leader should leave the stage. Conductor and orchestra trooped off, and the first Armstrong-with-British-symphony-orchestra venture was wound up.

Despite this unconventional finale the evening was most enjoyable and in many ways successful. The “straight” part of the proceedings went off well—interesting items admirably played—and the rest, because of Armstrong’s amazing magnetism and musical powers, was a knock-out. In themselves, the orchestrations were not ambitious—no real attempt being made to wed jazz and “legit.” It was simply, in “St. Louis Blues,” for instance, a concert arrangement of the two themes, then “St. Louis” swung by what Norman Del Mar referred to at rehearsal as “the jazz people,” and then Louis in and out of strings and a fast jazz finish.

Here, unhappily, Jack Parnell missed his break. No one else was upset, but I imagine it worried Parnell, because he drummed less well than he had done at both the rehearsals I heard.

Sid Phillips, too, seemed sometimes out of touch; but Dill Jones pulled out two or three nice solos, Chisholm played many excellent things, and Lennie Bush was in finest possible form—stimulated and not subdued by the occasion.

But it would be uncharitable to look for slips in a performance like this—hastily organised, under-rehearsed, and carried out in strange circumstances under the gaze of 80 pairs of Philharmonic eyes.

Armstrong felt it as a kind of climax to his career. He worked magnificently, quickly gaining in confidence and allowing his natural manner to intrude on what had been, up till then, a “serious” musical evening. The clash was felt more in the matters of showmanship, approach and audience response than in the music itself. Louis with strings has always sounded delightful, and though there were times when he and the orchestra got away from each other, they managed to finish together—more or less.

No complaints!

Singing and playing, Louis dominated the stage. I believe he threw a few surprises at his accompanists. But in the light-hearted atmosphere which by then prevailed, nobody was disposed to complain about an odd touch of chaos.

It was a triumph Louis, and he should have been brought back as the customers insisted. In fact, he was prevented, by some backstage forces, from re-emerging.

**********

Here’s a clipping of the United Press coverage of the concert, written by Robert Musel:

And here’s the transcription, with more juicy details:

“Louis (Satchmo) Armstrong blew the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and its angry conductor off the stage last night at a Hungarian relief concert that turned into a ‘shambles.’ A packed audience of highbrows and jazz fans—the mink and blue jean sets—created such an uproar that conductor Norman Del Mar gave up any attempt to complete the classical part of the program. He stalked off.

The uproar was so great Mr. Del Mar never returned to the podium and Satchmo was unable to deliver an encore. Even London’s lord mayor Sir Cullum Welch, was unable to make a speech of thanks.

The trouble started when Mr. Del Mar underestimated Satchmo’s great lung power. Mr. Del Mar, protégé of Sir Thomas Beechman and a most dignified British conductor had led the Philharmonic through Brahms’ ‘Tragic Overture’ and Stravinsky’s ‘Firebird Suite’ when Satchmo strode upon the stage with his magic trumpet. Mr. Del Mar gave the beat and his 80-piece orchestra started playing ‘St. Louis Blues.’ From then on, Mr. Del Mar should have stayed home.

After each number the crew-cut college crowd and the rock-‘n’-rollers roared their approval. The mink-and-tails set joined in and soon the joint was jumping. Mr. Del Mar went down fighting. As Satchmo finished his scratchy vocal of ‘Sleepy Time Down South,’ Mr. Del Mar held the orchestra on such a long note that Louis had to stop. Triumphantly, Mr. Del Mar ended the selection. Satchmo suddenly started singing an unscheduled chorus of ‘Back Home in Indiana’ and then groaned the sadistic lyrics of ‘Mack the Knife’ from ‘The Threepenny Opera.’

He sang spirituals and stayed on in response to commands from the crowd. Armstrong told the musicians they couldn’t resume the classical section of the concert ‘until we finish.’

So he threw in a few extra choruses. Mr. Del Mar abandoned all thought of getting around to Liszt.

‘I terminated the concert because it had ceased to be a concert and had become a shambles,’ Mr. Del Mar said.

‘The things the professor should have done was to stop the cats shoutin’ and play ‘God Save the Queen’ or something,’ Satchmo said.

He later said he wanted to return and play an encore but was stopped by impresario S. A. Gorlinsky.

‘He tore the horn out of my hand and said it was too late,’ Satchmo said.”

**********

Many versions of the United Press article ran a photo of Armstrong and Del Mar from before the concert; here’s one such clipping from the Los Angeles Herald-Express:

Louis Armstrong the Archivist came across multiple copies of the story featuring the photo of him and Del Mar and naturally Scotch-taped them into his scrapbooks (this first one also includes a blurb from February 1957 when a stick of dynamite was thrown at Armstrong’s concert in Knoxville….what an insane time in a life that had very few lulls):

While the drama with Del Mar was the focus of much of the coverage of the “Evening for Hungary,” Armstrong emerged unscathed, with many in the mainstream press praising every aspect of the trumpeter’s performance at Royal Festival Hall. This was something that was picked up by the Melody Maker in an editorial from January 5:

Here’s a transcription of the relevant portion:

LOOKING back at the Armstrong Festival Hall affair we are struck by two things apart from the magnitude of Louis’s own contribution, which has already been commented upon here and almost everywhere else.

The first is the general Press treatment given to Louis. Practically every big newspaper carried something about him and the concert. Many had features and news stories before and during his visit: several covered the musicians’ banquet (though none, so far as we know, reported the rather wonderful midnight departure of Armstrong’s party from Euston); and the News Chronicle made him the subject of its Saturday Picture and Verse.

In all, the treatment was fair and relatively factual. Naturally, reporters played up the angle of jazz driving the classical forces off the stage. It was a highly uncommon concert complete with a slap-up “story” finale.

But most writers gave Armstrong the best of it; and the total absence of references to Teddy Boys was an agreeable surprise. Even the stock rock-‘n’-roll phrases were discarded for the occasion.

It looks as though Armstrong has at last won through as a humorous man who can be taken seriously.

Needless to say, slips were made here and there. One daily reported that Louis would be playing his theme, “Happy Time Down South”; another said the programme would include the “Harry James Suite,” an obvious mis-hearing of “Hary Janos.” Someone even claims to have read that Armstrong was going to sing “Blueberry Pie,” but this was not seen by us.

At any rate, the great journals of the day revealed more affection for Armstrong than we had expected. And that expensive audience was undeniably for him, almost to a man.

Quite a drove of Pressmen descended on Armstrong after the concert to ask how he felt about being prevented from reappearing. Louis was restrained in his comments. But he admitted: “It’s a drag to have your horn taken out of your hands by some stage manager.” It must have been.

**********

The man tasked with assembling the best of the press coverage was Louis’s overseas press representative, and a famed jazz producer in his own right, Ernie Anderson. Anderson compiled three pages of “Extracts From Press Notices” about the Royal Festival Hall concert; here’s the first page, from our Ernie Anderson Collection in our Archives:

And for the last time (we promise–don’t worry, a bonus audio clip is still to come!), here’s a transcription of what Anderson considered the best of the best:

“That audience! It was the most extraordinary mixture of classical and jazz enthusiasts and just plain socialites I have ever seen. They had payed up to $30 to hear Armstrong – who had flown specially from Florida to play this one night in aid of Hungary. In a platform appeal for donations Sir Laurence Olivier talked about ‘this beautiful, noble character, Louis Armstrong.’ At 8.52 p.m. an attendant reverently placed a glass of water and a stack of white handkerchiefs on the grand piano in front of the assembled orchestra. Three minutes later something like a Hampden roar broke out as Louis Armstrong leaped on the platform, a banana-wide grin floodlighting his leathery face. But by the time he finished the concert was running 45 minutes late. They stamped, cheered and whistled for Armstrong to come back.” – Noel Goodwin in The Daily Express.

“Bright-sweatered teenagers sat beside min-draped society women cheering the jazz king. He had cancelled several thousand dollars worth of engagements in Florida for this one concert to aid Hungarian refugee funds. He flies home today. In the three thousand strong audience were Princess Margaretha of Sweden, the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Cullum Welch, Mr. Billy Wallace, Princess Margaret’s friend, and scores of debutantes. Armstrong sent the house into fevered applause with his variations the ‘St. Louis Blues.’” – The News-Chronicle .

“They shouted ‘We Want Satch’ after Louis Armstrong had rocked the Royal Festival Hall with his trumpet playing. He was accompanied by the sedate Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. Louis played and sang jazz classics and negro spirituals. And at the end of the celebrity-packed audience, their feet still tapping, called for more … and more. Louis – ‘The King of Jazz’ – had flown to England specially for the concert in aid of the Hungarian refugees’ fund. He said of his dress-shirted audience: ‘Man, they’re a snazzy bunch of cats. It was just like New Orleans in the old days.’” – Pat Doncaster in the London Daily Mirror.

“Louis (‘Satchmo’) Armstrong – in midnight blue tails – shows at the Royal Festival Hall last night what power a trumpet which is smooth and golden, confers upon a man. Satchmo had flown from the United States to play and sing as a gift to the Lord Mayor of London’s Hungarian and Central Europe Relief Fund. He was obviously very happy to be at the concert. He shone with musical exertion and good nature. He got a kick out of the industry of his jazz group – the experts parked in centre stage said the ranks of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra – when not occupied himself. When Satchmo sung half the audience was a-jerk. The woman next to me cooed and sighed blissfully as she twitched her fingers and smuggled into her furs. Satchmo and the orchestra did the “St. Louis Blues” stylishly. Then Satchmo and the jazz corps d’elite in mid-platform surged into ‘Indiana,’ a famous New Orleans number, with clarinetist Sid Phillips and trombonist George Chisholm improvising stirringly. From Satchmo came whirling cadenzas, exhilarating ornaments, trills of art and strength. And then Satchmo sang his signature tune ‘Sleepy Time Down South’ and spirituals. I report that everything Satchmo did was right by democratic weight of opinion as testified by hands and tongues.

Afterwards he told an admiring circle in his dressing-room, including Lord Mayor, Sir Cullum Welch: ‘You cats are sharp as needles. This show was just like we used to do it in the parks in New Orleans.’

Then Satchmo went with his wife, Lucille, Sir Laurence and Lady Olivier, film director John Huston and Lord and Lady Harewood to a party given by the Hon. Gerald Lascelles at the Dorchester.” – Percy Cater in the London Daily Mail .

“The music-minded turned out last night in evening dress, pullovers, windchesters, tartan slacks, crew cuts and peek-a-boo bangs. The motley crew filled the Royal Festival Hall for a concert in aid of the Lord Mayor’s Hungarian Relief Fund. After all, you cannot expect your audience to follow a set pattern when you bring Louis Armstrong and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra together on the same bill. On my right in Row 0 ($6.00) my neighbor was a young man in white ties and tails. On my left was a young lady wearing a sweater which proclaimed in black embroidery: ‘Live it up, Louis.’ The ultra-modern rafters of the Festival Hall really rang. That was when Louis Armstrong, rigged out in midnight-blue tails, strode buoyantly on to the stage to render with ferocity the St. Louis Blues. My neighbor in the flamboyant sweater pronounced herself: ‘Really sent.’ At work on a trumpet Armstrong’s face takes on the appearance of a dried prune. He perspires like a docker on piece work and calls frequently upon the supply of white handkerchiefs which lie on the piano behind him. He stands supremely confident in his patent leather shod feet and lets the ‘cats’ worship at them. Just before the interval Sir Laurence Olivier took the stage to speak in praise of Satchmo Armstrong. Armstrong, Sir Laurence told us, was a ‘beautiful, noble character.’ Nobody Know the Trouble I’ve Seen, and Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, then received the full Armstrong vocal treatment. Surprisingly, there was still sufficient breath left in the man to blow his trumpet through an item called simply Variations on Jazz Themes and which sent my neighbor in the sweater ‘into another world.’” – Ramsden Greig in the London Evening Standard.

“Armstrong, who received a tremendous reception when he appeared, played with the orchestra in a symphonic version of ‘St. Louis Blues.’ In the admirable acoustics of festival Hall, the clean and penetrating notes of Armstrong’s trumpet at times attained a wonderful beauty of tone. He added his characteristic embellishments of a nearly impossible character and the hall gave then full value. The strings of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra gave Armstrong’s trumpet the decent background it deserved.” – P.B. in the London Evening Star.

“Louis Armstrong had made a special journey from America to give his unique services for the concert with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in aid of Hungarian refugees in the Festival Hall last night. Both Satchmo and the R.P.O. seemed mildly surprised, and respectful, at each other’s presence. But Norman Del Mar held every force and every idiom together with the greatest skill. I am not qualified to assess Mr. Armstrong’s playing – I can only sit back and applaud a brilliance, virtuosity and charm that are irresistibly by any standards. He played his own Variations and many improvisations with untiring enthusiasm. He urged the group of British jazzmen to excel themselves. And he sang, with a voice of deep gravel, three spirituals (including the splendid ‘Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego’) as well as producing what the programme note nicely described as ‘slightly inarticulate vocalising.’ His personality was warmly saluted by Sir Laurence Olivier. – J.W. in the London Daily Telegraph.

“Wearing midnight-blue satin tails, Louis ‘Satchemouth’ Armstrong, the world’s greatest trumpeter, stepped on to the stage of London’s Festival Hall last night. He stood fiddling with the keys of his trumpet while conductor Norman Del Mar led the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra into a symphonic arrangement of ‘St. Louis Blues.’ Then Louis, putting his trumpet to his lips, cut loose with a real New Orleans version of of the number, leading a bunch of picked British jazzmen. When the two groups got together at the end of the number the symphony was really swinging. The fans went crazy with delight. But the members of the symphony were lapping it up.” – Kennedy Broom in the London Daily Herald.

“The Royal Festival Hall is creating a reputation for itself in music as fresh and unusual as its own situation. Mr. Louis (Satchmo) Armstrong, the King of Jazz, and a great virtuoso of the trumpet, plays with one of the finest orchestras in the world, the Royal Philharmonic. The conductor, Mr. Norma Del Mar, who, like the orchestra itself, has won renown under the tutelage of Sir Thomas Beecham, has never attempted anything of this kind before. Armstrong who speaks the language of jazz in his gravel voice encouraged the Royal Philharmonic with words Sir Thomas never used: ‘We’re sold – Grab it, cats.’” – Seamus Kelly in the Dublin Irish Times.

“Every tune played or swung by the star won a tumultuous reception and Sir Laurence Olivier’s tribute to him in an interval speech only underlined the mood of a whole intoxicated audience. A triumphant evening for one of the world’s most warmly loved and blasingly distinguished artistes.’ – Mike Butcher in the New Musical Express, London.

**********

That concludes Anderson’s compilation of press clippings about the London show, but Anderson is also involved in what will be the grand finale of this Virtual Exhibit: a reel-to-reel tape Louis made after the concert offering his reflections about that night at Royal Festival Hall and thanking all of those who made it such a special occurance. Anderson is present in the background during the making the of the tape–Armstrong mentions him–and I have a hunch that we might have another artifact in our Archives that was present during this recording. In one of Jack Bradley’s scrapbooks is a letter from someone at the Daily Mirror addressed to Anderson on December 17, the day before the concert:

But on the back of the letter are the names of the British musicians in the band that backed Armstrong up at the concert:

During this recording, Armstrong clearly reads the names of the British musicians who accompanied him. Jack Bradley wasn’t on the scene yet so knowing how much of Louis’s stuff ended up in his collection later on makes me wonder if the above page is what Louis was holding when recording his message. Either way, it’s a touching postscript to this epic tale (and a bonus, Armstrong discusses his 1920s feature on Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana–and even scats a few bars of the “Intermezzo” the way he used to play it with Erskine Tate!):

With that, we finally conclude this Virtual Exhibit on one “climax” in a career filled with them. This one has flown under the radar for far too long so if you’ve taken the time to listen to the audio of the concert and read all the clips, please leave us a comment to let us know what you think!